You should know up front that you have the choice to not parti-gyle but say that you did. You would be a liar, of course, but you would still get to enjoy one of the benefits of parti-gyling as a homebrewer—that is, getting to say that you did it—without actually adding extra boils to your brew day or doing all the math.

Now that you have been advised, we will assume that you are an honest person and not a liar. Good for you! Let’s continue.

In short: Parti-gyling means getting multiple beers out of the same mash. The brewer boils successive runnings separately, and then, ideally, blends them to different strengths.

For the average homebrewer, this appears to be slightly insane. One mash/one boil works well enough, and our time is precious. Why add extra boiling and chilling, not to mention extra pots and fermentors?

For brewers of a certain era, however, parti-gyling was the sensible thing to do. It had clear advantages. And for commercial brewers with the right setup, it still has those advantages today. For today’s homebrewers, it is just one more tool in the toolbox, but those advantages still come into play (and we’ll get to the advantages shortly).

While the technique is not especially complicated, much of what has been written about parti-gyle has either been too simple—leading to common misconceptions—or more technical, glazing the eyes with gravity figures and ratios. Here we aim for the middle way: clear but accurate.

Also, we will get valuable guidance from John Keeling (above), head brewer at London’s Fuller’s Brewery, producer of arguably the best-known parti-gyled beers today. We went all the way to Chiswick, West London, to ask him about it and snap pictures of him in one of those fetching safety vests. As he says, “[Parti-gyling] is the most efficient way to get the most out of your mash tun.” He ought to know; he has been doing it since 1981.

Parti-gyling is an old method, used for centuries, to get more beer(s) out of the same grains. The usual but not-quite-right way to describe it is that you make one beer out of the stronger first runnings, another beer out of weaker second runnings, and possibly even a third or more beers from additional runnings.

Technically, that counts. “Separate runnings is legitimate parti-gyling,” Keeling says. But that’s the crude way, and it ignores roughly 230 years of better practice. Keeping those worts separate means that you miss two of the great advantages of this technique: blending worts _to hit target gravities, meanwhile making _more types of beer.

To illustrate how it works, Keeling describes an approximation of a typical run at Fuller’s. He brews two worts from the mash—the first runnings hit about 1.080 gravity, while the second runnings come in at about 1.020. At least three beers come out of those two worts: Extra Special Bitter (ESB), London Pride, and Chiswick Bitter, going from strongest to weakest. Each beer is a blend of both worts. (Sometimes the same mash also produces Fuller’s stronger ales, such as Golden Pride or Vintage Ale. Even those beers get a small portion of the weaker wort.)

The ESB typically starts between 1.050 and 1.060, depending on whether it is for cask or bottled for export. London Pride—by far Fuller’s most popular brand, representing three of every beer sold—starts near 1.040. The beautifully subtle Chiswick Bitter, mainly meant for cask at about 3.5 percent ABV, starts with a gravity near 1.035. Basically, having worts of strengths that are both high and low lets Keeling blend them and nail those target gravities every time.

Why do it like this? For consistent products and for efficiency in the brewhouse. “Consistency is really important,” Keeling says. “I want [the beer] to have personality and character in there, so it does tell me something different from time to time. . . . We have standards and values here about how to make beer. The observations and what they do, that’s what makes the difference.”

Later I ask Keeling to clarify that idea—the balancing of consistency and personality. “The first thing I want a drinker to do is recognize the beer. Then the beer’s character reveals itself through the years of drinking,” he says. “Consistency comes from the [brewery] and its use, but in brewing there are lots of individual decisions to be made.” For example, how long should the brewer recirculate wort before starting runoff? When should the brewer stop the runoff? Based on gravity and other observations, should the mash temperature be tweaked? Should the mill setting be adjusted?

And about that efficiency? Keeling says the second wort is really allowed to run until the extract gets as low as 1.005. “[We] get everything [we] can out of the mash tun.”

After blending, the beers diverge further during maturation. The ESB spends two to three weeks maturing, with hops in the tank. The London Pride is matured for a week but not dry hopped. The Chiswick gets a week and is dry hopped.

And there, in that variation, lies the other major benefit of parti-gyling: the _flexibility _to make many different beers from the same mash. For homebrewers unbound to tradition or branding, the possibilities are practically infinite. Hop the worts differently. Boil one of them longer. Give them different yeasts. Ferment them at different temperatures and for different lengths of time. The only thing not easily changed, of course, is the grain bill, although it is possible to cap later runnings with extra malt or to add sugar, thus allowing changes to color, flavor, and strength.

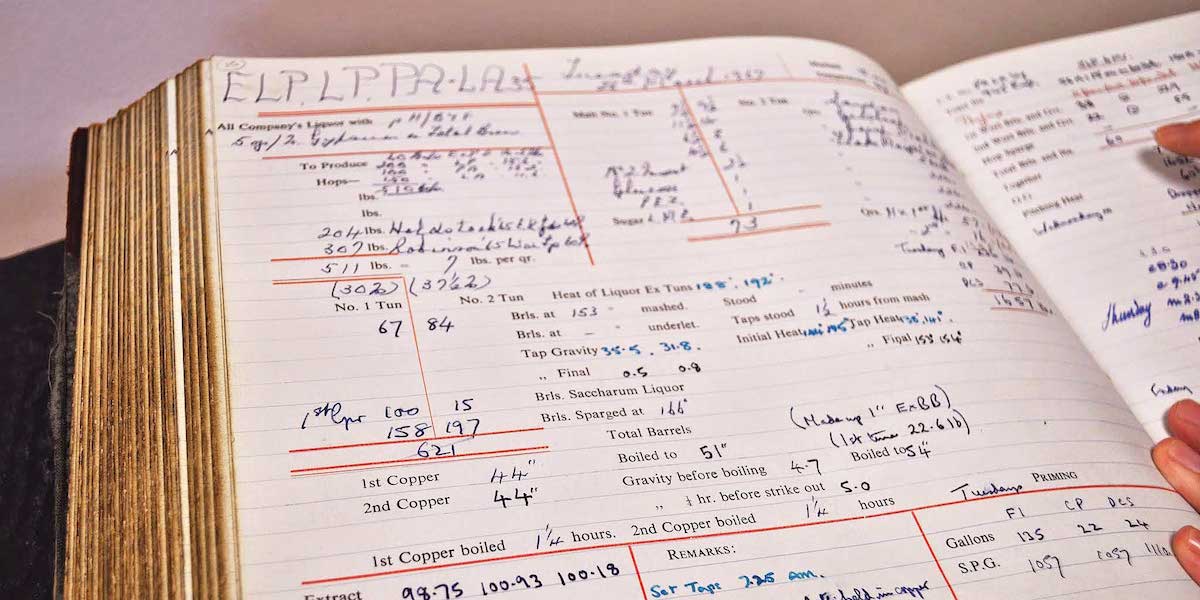

Keeling refers to parti-gyling as a “particularly Victorian way of making beer.” What does that mean exactly? In this context, it means “practical and industrial.” The Victorians inherited early industrial techniques—then they improved them. The cost of malt was high relative to wages. Meanwhile pubs and drinkers were apparently accustomed to a wide range of beers to suit preference or occasion. Parti-gyle was not a trick in that environment; it was common practice that had improved over time.

Modern homebrewers, meanwhile, typically don’t mind spending extra on malt—we know our hobby costs money; we are not in it for profit. Free time for additional boiling and chilling, on the other hand, can be hard to come by. And for those of us using gas burners, propane isn’t cheap either.

But if you’re interested in historical beer and brewing techniques, are motivated to produce greater variety, have extra free time and/or additional vessels (which can help trim the extra time needed), have a fetishistic love of arithmetic, and/or are usually sober toward the end of the brew day, parti-gyling may be just the technique for you.

For my part, I have parti-gyled a couple of times (really!). The beers turned out nicely, thanks, but if I’m honest with myself—and I am nothing if not honest, sirs and madams—I did it mostly just so I could say that I had.

Sorry, Did We Say There Would Be No Math?

This is for extra credit then.

Parti-gyling is less intimidating if you are not fussy about target gravity, but I know some of you want to predict everything on paper and then nail it on brew day. You have my admiration, because I am the type to predict everything on paper then completely miss it on brew day, taking notes to record it with the hilarious notion of repeating it in the future.

We’ll go with Keeling’s example of two worts of 1.080 and 1.020, respectively. With those worts you’d like to make three beers of varying strengths—let’s say an IPA at 1.070, a mid-range pale ale at 1.050, and a saison of 1.040.

How do you make that happen? This is where the math comes in. The simplest way to do the math is to use the gravity points—80 and 20—in per gallon terms. Let’s assume you draw 5 gallons of each wort, so your total points are 400 and 100 respectively (80 × 5 = 400; 20 × 5 = 100).

Are you with me so far? To get 2 gallons of 1.070 wort (for the IPA), we want 70 points per gallon or 140 points. The way to get there is to blend 1.67 gallons of the stronger wort with 0.33 gallon of the weaker one. Okay, I’ll show my work (and there will be some rounding):

1.67 × 80 = 133.33 and 0.33 × 20 = 6.67

133.33 + 6.67 = 140

140/2 = 70

You get the idea. The next one is easy. When you take 2 gallons from each wort you get a neat 200 points, divided by 4 gallons to make a tidy 1.050. There’s your pale ale.

That leaves 4 gallons—1.33 gallons of strong stuff to blend with 2.67 gallons of lighter stuff. You end up with 4 gallons worth 160 points, and there’s your 1.040 wort for your saison.

That’s an illustration. It’s not necessary to nail your 1.080 and 1.020 gravities in the first place, as long you’re ready to do some math with what you have. Also be aware that these are post-boil gravities, as the boil will concentrate the strength somewhat.

There are other ways to be flexible: For example, hit your targets on two of your beers but take whatever you get on the third; or, hit all three of your targets without using all of your wort, saving the rest for a yeast starter or some other use. Now, go parti-gyle! If you like, you can start with this recipe for No-Math Parti-Gyle Old Ale, IPA, and ESB.

More About Fuller’s Brewery

Fuller’s Brewery is not the only British brewery that parti-gyles, only the best known. That might be because Fuller’s does a better job than most of welcoming visitors and telling its story.

Walking through the posh district of Chiswick—with its trendy coffee shops and $8 million homes—one turns a corner near the river and finds a strategically preserved piece of the nineteenth century. With its red-brick buildings and respectable smokestack, the Griffin Brewery of Fuller, Smith and Turner has been a cornerstone of this community for at least 170 years. In fact, brewing has been going on at the same location since the 1500s.

One symbol of its pedigree is a famous wisteria plant that clings to its offices (above). This is said to be the oldest wisteria in Britain; it began as one of two clippings that arrived from China in 1816. The other went to the Royal Botanical Gardens but later died.

Fuller’s is aware of its status as an attraction, offering frequent tours and a well-stocked brewery shop. Tours start next door at the Mawson Arms pub, which itself dates to 1715.