Ask for anyone’s short list of beer flaws and invariably you will hear “DMS—dimethyl sulfide,” bested only by the other D-word “diacetyl.” Unlike diacetyl, which is created during fermentation, the cause and cure for DMS happen before yeast ever touches the wort.

For those who have never had the pleasure of encountering this “flavor attribute,” DMS is often described as a cooked-corn flavor, but you may also be reminded of the inside of a can of black olives or canned tomato paste. If you ever have the chance to taste a particularly potent example, you may be able to then find it in a surprising number of beers, both commercially brewed and homebrewed.

DMS is a sulfur compound that is created by s-methylmethionine (SMM) sometimes called simply “DMS precursor.” SMM develops during the germination of barley and is therefore present to some degree in all malt. Most of it, however, is broken down to DMS during malting and is volatilized during kilning. The darker the kiln, generally the lower the SMM level in the finished malt. Very pale malt such as Pilsner, however, still contains appreciable amounts of SMM, which breaks down into DMS when exposed to the heat of the boil. That makes it tricky to get a DMS-free very light colored wort using 100 percent barley (using adjuncts such as corn and rice can decrease the SMM/DMS load). In this article, I discuss a novel approach that attempts to do just that.

Looking for DMS

Research suggests that DMS is generated somewhere around 120°F (49°C) or higher but is not volatile until about 165°F (74°C) and above. The general practice to eliminate DMS involves ensuring a long and open boil to allow the DMS to escape over 75–90 minutes and then to chill the wort quickly to below the 100°F (38°C). Generally this will produce DMS-free beer, but we homebrewers with direct-fire kettles will also see at least some darkening of the wort in that long boil. The question arises: can we break down a maximum amount of SMM into DMS before the boil and keep our color low without introducing flaws in the finished beer?

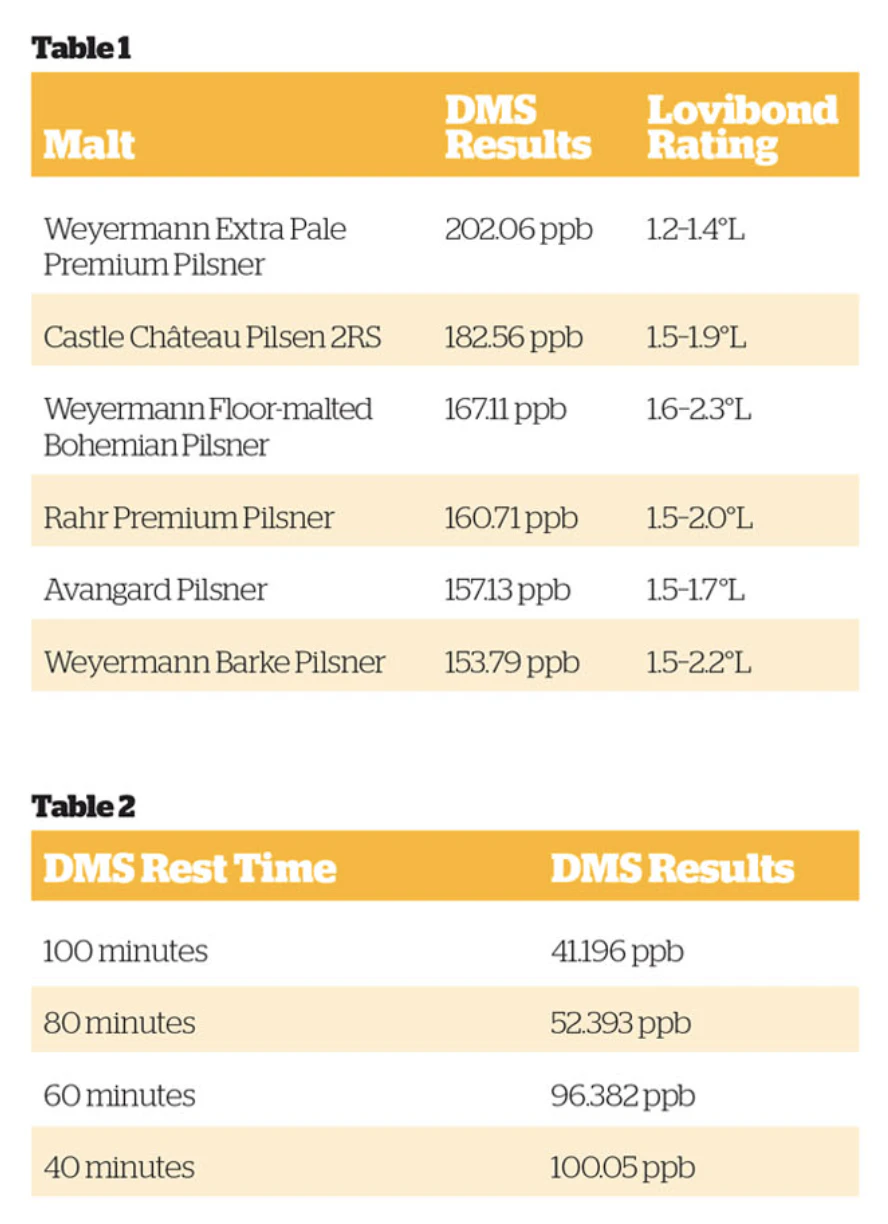

To find out, I first brewed six “DMS train-wreck beers” using different brands of Pilsner malt to find the worst offender. The good people in New Belgium Brewing’s lab, Dana and Jeff, were kind enough to humor me, running them all through their gas chromatograph. The attempt, as shown in Table 1 (below), was an unqualified success. If we consider that the accepted threshold for tasting DMS is 35 ppb, these are all ridiculously high. It’s interesting to note that the worst offender, Weyermann Extra Pale Premium Pilsner, is also the one with the lowest Lovibond rating. At only 1.2–1.4°L, there is simply more unconverted SMM for me to reckon with. It is also mildly interesting that the floor-malted sample is slightly higher than the Rahr, despite being kilned a touch darker. Perhaps it has something to do with the peculiar malting process involved. Or perhaps it was just this sample.

Generating and Volatizing DMS

Having identified the worst-case malt, I proceeded to the second stage of the experiment, which was to try to generate as much DMS as possible pre-boil and attempt to gauge how long of a boil was necessary to volatize it sufficiently. I used a 100 percent Pilsner malt mash, acidified for conversion. After the usual vorlauf and lauter, I allowed the wort to stand at 160–180°F (71–82°C) for what we’ll call a “DMS rest.”

After 40 minutes of DMS rest, I pulled off a quarter of the wort and boiled it for 20 minutes, then cooled it with a copper immersion chiller to below 100°F (38°C) in just about 30 minutes. Then I pulled off another quarter of the wort every 20 minutes up to 100 minutes, and I boiled each quarter for 20 minutes and cooled it in 30 minutes. Mind you, 30 minutes is considerably slower than I would normally chill, but my hope was that I would leave behind a measurable amount of DMS to contribute any reduction to the length of time in the “DMS rest.”

The resulting beers were (understandably, given the short boil time) all impressively light in color, but would they be drinkable? Table 2 shows the results, again run through New Belgium’s lab. As you can see, the longer the wort was allowed to stand pre-boil, the greater the reduction of DMS in the finished beer. Although most tasters would detect DMS even in the sample with the lowest DMS level, the variance among them is wonderfully telling.

The final test is, of course, to produce an actual beer using both a conventional lauter and 90-minute boil and using a 100-minute DMS stand and a 20-minute boil time (chilling them much faster!) and compare flavor and color development.

My theory (based on the evidence) is that given a direct-fired boil, letting the hot wort stand beforehand will still allow dramatic DMS production and volatilization with a very minimal boil time and should produce the lightest color possible on a given system. It would be interesting to further investigate the time needed to generate 100 percent of the available SMM-to-DMS and then just how short a boil is necessary to be rid of it. It’s feasible that given enough time before and during boil, the problems of a slower chill method could be greatly mitigated. Lucky for us, there is always more research to be done!