Who doesn’t love fruit? Its sweet lusciousness and acidic balance drive us to near-delirium. Why wouldn’t we want to put those exciting flavors into beer?

Almost as soon as brewing began, people started doing just that: hawthorn fruit in Neolithic China; cranberries and lingonberries in Bronze Age Sweden, and more. It’s not clear whether fruit beer persisted through the Middle Ages, but Heinrich Knaust mentions a kirsch (cherry) beer in 1614. As far as I can tell, fruit beer never achieved dominance anywhere in Europe over the past couple of millennia. Instead, here and there, it was a seasonal specialty; fruit is highly perishable, and freezing and pasteurization weren’t viable until modern times.

In the original canon of “classic styles”—think Michael Jackson’s early writings—cherried versions of Belgian lambic and oud bruin were the only fruit beers. They were modestly popular at least by the 1930s but are possibly much older. Early U.S. microbrewers added fruits to their easygoing American wheat ales with some market success, such as with the apricot version from Seattle’s Pyramid Ales.

Since then, there have been several waves of fruit beers with a wide variety of interpretations—from kettle-soured gose and Berliner weisse to sour and fruited IPAs and the almost impossible slushy beers inspired by convenience-store treats.

Components of the Fruit Experience

To one degree or another, fruit beers try to replicate the soul-absorbing experience of fresh fruit. It isn’t easy. No matter what a brewer does, it’s impossible to fully re-create that because beer is—by definition—mostly non-fruit. A convincing fruit beer pulls enough fruity levers for us to recognize it as fruit.

Let’s follow the senses. Fruit aroma is laden with fruity-smelling ester molecules, often with other chemicals: lactones (peaches, strawberry), ketones (raspberry), super-potent sulfurous molecules called thiols (tropical fruits and sauvignon blanc grapes), and others.

Fruit’s dramatic visual character isn’t just a show—it sets the brain up for what’s coming. If you simply color plain, sweetened water with food coloring, tasters will perceive it as fruity. (That’s why wine is often judged in black glassware.)

In the mouth, fresh fruit assaults the senses. Acidity registers quickly, followed by sweetness and rich mouthfeel, followed by tannic astringency. Upon exhalation, retronasal smell presents a different kind of aroma, both chemically and psychologically, as fruity-smelling chemicals are released by salivary enzymes and the brain reroutes the input through circuits involved with edibility and familiarity.

The personality of fresh fruit depends on a specific mix of these sensory characteristics. Because of the brain’s multisensory processing of flavor, each component supports the others based on stored memory templates. It doesn’t require a perfect match to identify the fruit. That’s a key insight: Get as close as you can manage, and let the brain do the rest.

Simulacra and Simulation

Sadly, we are no longer as close as we once were to fresh fruit. Grocery-store versions are created to travel well and look good, with flavor considerations a distant third. Lack of access to real fruit, such as strawberries, has allowed grocery-store stand-ins and strawberry-flavored candies and pastries to create a real jumble. Beyond this, abstract flavors such as “blue raspberry” don’t exist in nature, yet they become part of our internal libraries of fruit flavors.

Fruits in beer differ in the clarity of their character. Raspberry is almost always identifiable. Some, such as peaches and strawberries, transform during fermentation or aging, altering their character. Others, such as watermelon, defy efforts to make a natural-tasting flavor extract (though many are familiar enough with the artificial watermelon-candy taste). One of the best fruit beers I ever tasted was made from strawberries scooped from barrels that spilled out of a derailed freight train headed to a Smucker’s jam factory. With free fruit, cost was no object, so the homebrew-club members used as much as they could. I had the luck to taste it when it was fresh.

What to use? Craft breweries often use aseptic fruit puree, juice, or concentrate, since they’re manageable and pretty close to fresh. Whole fruit is another option, but it requires specialized processing. At 5 Rabbit Cervecería in Chicago, we once used 2,200 pounds (about 1,000 kilograms) of watermelon in a summer wheat beer, cut and processed by hand using a giant stick blender—but just once. At Forbidden Root (also in Chicago), we’ve gotten good results from adding freshly squeezed juice to half-barrel kegs. This makes for amusing variants of house beers, but it’s difficult to scale and just about impossible for a small brewery to package safely.

Adjusting the Base Beer to Favor Fruit

Since a typical fruit beer is less than 10 percent fruit, there’s more in the flavor mix to consider. Each fruit beer has a base, whether it’s a known style or unique formulation. There are classic brewpub wheat ales; kettle-soured beers inspired by gose or Berliner weisse; new-era sour/tart IPAs; wild, barrel-aged, or Brett beers; plus a few super-intense fruit beers of which New Glarus’ Wisconsin Belgian Red is the poster child. However, there are many other avenues.

It’s important to pay attention to how the fruit and base beer work together. At the least, the beer should not interfere with the fruit—but it’s possible to create some real magic. The cookie character of Munich malt plus cherries? Cherry strudel. Black malt and raspberries? A nice impression of a raspberry truffle, if they’re intense enough.

Hops and fruit are a fascinating challenge. We don’t generally associate bitterness with fruit, but sweetness and acidity can mask or obscure it. Newer hops offer loads of tropical, citrusy, and other fruit-friendly flavors—they make great dry-hop additions, even for non-IPAs. And, of course, the hazy-juicy IPAs are pretty close to fruit-ready if the hops are chosen thoughtfully.

A Sense-by-Sense Summary

There are plenty of challenges for brewers, but that’s what keeps it interesting. Whether taster or brewer, I think it’s always important to try to pull apart the senses. It’s especially important here, where there are so many interacting parts.

Aroma

Each fruit has a specific mix of odor molecules. In commercial flavoring contexts, they use a brute-force chemical deconstruction via gas chromatography, separating the components and determining their importance—then they blend to re-create it.

In the brewhouse, we can do something similar: Add a little rose to boost a key aspect of lychee; add some juniper to punch up the resiny aroma of mango; add a little sweet osmanthus flower to really reinforce peachy aromas. Some ingredients also are harmonious with particular fruits for whatever reason and can help to emphasize them: tarragon and pear; a hint of cinnamon or clove with cherries; chamomile or elderflower with white fruits. For clues, look to pastry cookbooks.

Natural “top-note” aroma extracts are best used to reinforce what’s already there. Asking them to do all the heavy lifting is just too much, leading to an aroma that seems thin or artificial.

Acidity

There is a reason why acidic base styles have arguably become the default for fruit beers.

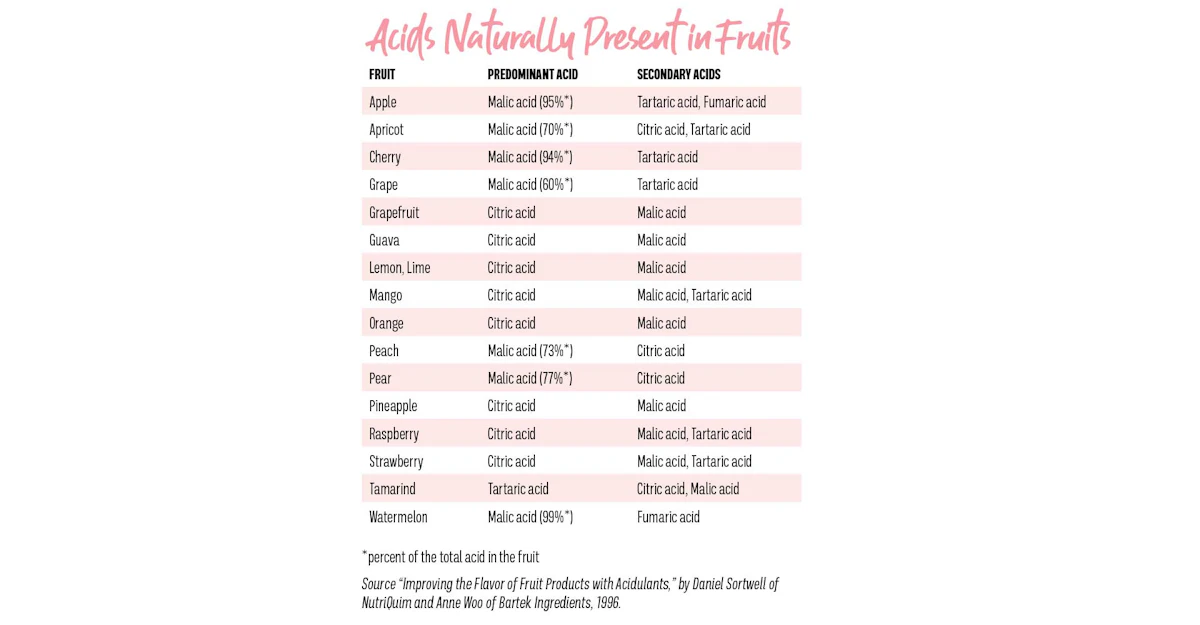

Each type of acid found in fruit has a different sensory character as well as a different intensity of sourness (see the fruits and acids chart below). Checking pH is useful for normal brewing calculations, but it falls apart as a measurement of intensity in sour beers. Each different type of acidity has a different amount of access to sour-taste cells.

For example, at a given pH, citric acid tastes more sour than lactic and others. Different acids interact with the trigeminal (mouthfeel) system, adding pungency in the nose and throat. Acetic (vinegar) acid is particularly potent in this regard. Citric is sharp as a razor; malic (apples, grapes) has a bit of a raspy edge; lactic is typically not found in fruits, coming instead from lactic fermentation, and it has a smooth, dairy-like creaminess.

Each specific type can add to or detract from the specific fruit character you want. Also, keep in mind the sourness of the fruit: Too much tartness in a pear or watermelon beer can push it into unrecognizability. If you’re brewing, it’s easy to do tabletop tests to find the right amount and kind for correct intensity and character.

Mouthfeel

Some fruits have a smooth, creamy texture. You can boost that impression by using wheat, oats, or rye, which add glucans and other slippery carbohydrates. On the flip side are tannins, often coming from red and purple fruits, or by contact with oak in fermentation or maturation. In sour beers, these can add a valuable counterpoint to acidity, as they do in wine.

Sweetness

Sweetness is challenging. In most cases, it’s essential to ferment the fruit sugars completely to prevent fermentation in the package—but this removes their sweetness.

Mashing warm can create unfermentable carbs. Lightly caramelized malts (Vienna, Caramel 10) also can boost sweetness. So can unfermentable lactose, but at higher amounts, it can taste artificial. A little licorice root can add sweetness and mask hop bitterness. Boosting fruity aromas can also help, so an estery yeast can be useful. A new thiol-producing ale yeast meant to boost tropical hop notes should enhance beers based on tropical fruits. Rye has a cherry-like fruitiness that’s nice with red fruits. We invariably associate vanilla with sweetness, so it can help if you don’t mind veering off into candy-land.

Color

Color molecules are anthocyanins and other tannic molecules, ranging from orange to purple; these often add some pleasant astringency as well. You can deepen color with additions of hibiscus or dark fruits such as elderberries. A huge problem is that many fruit and natural colors are unstable in beer and will fade, often rapidly. In addition, pH can affect hue, with low pH making hibiscus more magenta and less scarlet. It’s often helpful to make the beer a shade or two deeper than desired, knowing that by the time it hits the market, it will fade a bit. If you’re brewing pink beers, keep the malt color to a minimum; beer’s yellowness tends to drag it into the orange zone.

Fruit beers are fun. They’re also among the most complex and challenging beers out there, forcing both brewers and drinkers to take in their huge range of different sensory characteristics. It’s worth the trouble because fruit beers can be among the most profound and meditative beverages you’ll ever sip.