In the uber-dramatic introduction to the Discovery Channel’s trail-blazing 2011 documentary How Beer Saved the World, lightning flashes, fires rage, wort bubbles, and beer historian Gregg Smith tells the camera, “Beer has changed the course of human history. Not once, not twice, but over and over again.”

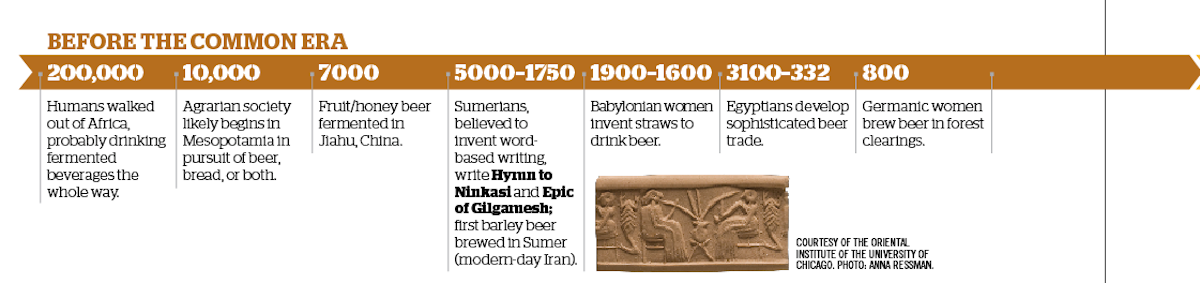

Calling it “the greatest invention of all,” the film producers credit beer for helping to originate math, commerce, modern medicine, refrigeration, automation, and even the first system of non-pictorial writing. As they explain, our literal dependence on beer and earlier forms of alcohol has likely shaped fundamental aspects of human existence for 200,000 years. Yet the producers ignore the fact that, until fairly recently as history goes, women were the driving force behind much of the world’s beer production.

Of Goddesses and High Priestesses

“Ninkasi, you are the one who pours out the filtered beer of the collector vat; it is [like] the onrush of the Tigris and Euphrates.”—Hymn to Ninkasi

In 2004, archeologists placed the discovery of the world’s first fermented beverage (a mixture of fruit, honey, and rice) in Jiahu, China, between 7000 and 5700 BCE. The finding overturned the conventional wisdom that humans had concocted their first grain-based drink in ancient Mesopotamia, located in modern-day Iran and Iraq. Historians now qualify the Mesopotamian concoction as the world’s first barley beer and remain committed to their original belief that civilization began in this so-called “fertile crescent” between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers.

They date the evidence found in the Mesopotamian state of Sumer to no earlier than 3500 BCE but are confident that the world’s first settlers began growing barley for beer and/or bread as early as 10,000 BCE. Many suspect the hunter-gatherers who preceded Sumerians on the evolutionary timeline also brewed beer, accidentally creating the intoxicant in containers filled with airborne yeast and rain-soaked wild grains.

Though they argue over the ancient origins, archeologists who study fermentation do agree on one thing: the vast majority of ancient brewers were women. “While men were out hunting, women were out gathering the ingredients they needed to make other foods and drink to go with the wooly mammoth or mastodon,” says Dr. Patrick McGovern, the University of Pennsylvania biomolecular archeologist who determined that the Mesopotamian drinking vessels contained the earliest known barley beer.

Once our nomadic ancestors realized they could revolutionize their lives by planting barley, wheat, and other grains, they permanently came in off the road. But they didn’t necessarily change the divisions of labor. “Women [were] the ones who [made] the household fermented beverages,” McGovern says of those early societies.

Sumerian women brewed low-alcohol beer for religious ceremonies and as part of the daily food ration. Sumerian brewers enjoyed tremendous respect, in part because they probably also served as priestesses of the revered beer goddess, Ninkasi. Sumerians believed Ninkasi oversaw the brewing process and “worked” as head brewer to the gods, who’d gifted beer to humans to preserve peace and promote well-being. They showed their reverence in the _Hymn to Ninkasi, _history’s oldest written beer recipe.

Two thousand years before Jesus and around the same time that invaders vanquished Sumer, the Mesopotamian city of Babylon ascended by building on its former neighbor’s accomplishments. Like their predecessors, Babylonians held women in high esteem. Babylonian women enjoyed the right to divorce and own business and property, and some historians say they may have participated in some of the world’s earliest commerce as they sold their beer with new forms of bookkeeping and writing. Women were encouraged to work as tavern keepers and professional bakers/brewers.

Archeologists hold that Babylonians or Sumerians introduced brewing to their neighbors, the Egyptians. Egyptians worshipped a goddess of beer named Tenenit and told stories about the goddess Hathor/Sekhmet who saved humanity from destruction after a binge. Hieroglyphics depict women brewing and drinking beer through straws, which historians say the Babylonian brewers probably invented to pierce thick layers of scum that floated atop their product.

At first, Egyptian brewing likely fell to the women of the house. But records suggest that as “production” breweries spread across Egypt, men replaced women as brewers, and those women were pushed into secondary roles. This corporatization of breweries may have carried Egypt and its most iconic female ruler toward their demise. As the online Ancient History Encyclopedia tells us, Cleopatra, Egypt’s last Pharaoh of consequence, “lost popularity toward the end of her reign more for implementing a tax on beer (the first ever) than for her wars with Rome, which the beer tax went to help pay for.”

Brewsters, Witches, and the Beginnings of Capitalism

In Baltic and Slavic mythology, a goddess named Raugutiene provides heavenly protection over beer. Finnish legend recounts that a woman named Kalevatar brought beer to earth by mixing honey with bear saliva. And while Norse folklore indirectly credits a man for beer, the late beer anthropologist Alan Eames wrote in 1993 that real Norsemen (a.k.a. Vikings) allowed only women to brew the “aul” that fueled their conquests. In an article published in Yankee Brew News, Eames noted, “Viking women drank ale, flagon for flagon, along with the men.”

Early Northern Europeans worshipped their beer goddesses as ancient Middle Easterners did, and before the second millennium CE, most European women drank and brewed beer. From migratory Germanic women who brewed in forest clearings to avoid Holy Roman invaders to the English alewives who maintained their traditions until the Industrial Revolution, European women fed their husbands and children low-alcohol, nutrient-rich homebrew that proved more sanitary than water.

For thousands of years women brewed an unhopped liquid called “ale,” whose quick spoilage rate suited decentralized domestic production. Some entrepreneurial female brewsters (the feminine equivalent of the masculine “brewer”) produced more than their families needed and sold the surplus for a pittance. But married women held no legal status, and unmarried women held little capital. Their predicament left them financially and politically vulnerable and unable to access the economic developments and technological advancements that gradually transformed Europe from an agrarian society to a commercial one.

German nunneries provided a rare shelter for single women to blossom as brewsters and botanists, with St. Hildegard of Bingen distinguishing herself as the first person to publicly recommend hops as a healing, bittering, and preserving agent some 500 years before mainstream society took heed. Outside monastic walls, a brewster’s right to self-determination lay at the mercy of feudal lords, the Church, or the emerging merchant class—whichever element or elements held sway in her particular time in her particular region.

The mainstream discovery of hops in sixteenth-century Germany gave the ruling classes more leverage to outlaw dangerous beer additives that brewsters had used for centuries. Granted, purity laws such as Reinheitsgebot undoubtedly kept at least a few drinkers from dying. But they also put higher-cost resources such as hops out of brewsters’ reach. With hops also came longer-lasting beer. Men reacted by building production breweries and forming international trade guilds. Law and custom kept women out of both.

Meanwhile, as the Dark Ages gave way to the Renaissance and the Age of Exploration, brewsters weren’t just losing relevance. At a time when, by some estimations, up to 200,000 women were prosecuted as witches, they were losing their dignity and their lives.

Depictions of brewsters in art, literature, and pop culture swung negative. And although no one can prove a connection, some historians see clear similarities between brewsters and illustrations selected for anti-witch propaganda. Images of frothing cauldrons, broomsticks (to hang outside the door to indicate the availability of ale), cats (to chase away mice), and pointy hats (to be seen above the crowd in the marketplace) endure today.

“In a culture where beer defines part of the national character, the question of who controls the brew is paramount,” observes a writer for the German Beer Institute. “He who has his hand on the levers of power, also has his thumb in the people’s beer mug.” By 1700, European women had all but stopped brewing.

Seeking a New Life in America

Maybe you’ve heard the story about the Pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock because they’d run out of beer and needed to build a brewhouse immediately. Well, it’s bogus. It’s true that the trans-Atlantic voyagers did bring beer rations across the sea and that they didn’t trust the water supply in their adopted homeland because they knew the water back home to be unsafe. But beer rations aboard the ship held up just fine during the journey, and the first thing the settlers built were huts to shelter against the cold.

However, the truth is that once the men built permanent housing, they each built their wives a kitchen brewery. In colonial America, as they had in Europe, married women homebrewed “small beer,” which they supplemented with cider, to sustain their families.

As the colonies urbanized, city men conducted their business and pleasure in taverns provisioned by regional commercial breweries. But in rural areas, homebrewing remained the dominant source for beer for more than a century, and it wasn’t Thomas Jefferson who merited acclaim as a brewer, as folklore would have us believe. Instead, his wife, Martha, enlisted slaves at Monticello to brew her regionally famous recipes for wheat beer.

However, as in the past, “When money got involved, men increasingly started brewing,” says Gregg Smith, who wrote the book, Beer in America, The Early Years: 1587–1840. “As the industry developed, it went that way even more.”

Louis Pasteur’s 1857 discovery of yeast coincided with a massive wave of German immigration, which brought lagers, refrigeration, cheaper packaging, and rail delivery to an at-once expanding and consolidating full-scale brewing industry. No law kept women out of these factories, but the mores of the time prevented them from entering. However, the Germans’ more relaxed drinking culture did introduce family-friendly bier gardens to America, and proper women in East Coast and Midwest population centers were coaxed outside to drink publicly for the first time. This “cavalier” approach to drinking incensed the leaders of the Temperance movement.

Though low-alcohol lager offered a relative respite from the destructive impulses of rum, Prohibition extended breweries no reprieve. Beer brewing (illegal) crept back inside the home, where women, such as Smith’s coal-country grandmother, kept the tradition going. “They kept doing what they’d been doing,” Smith says.

It’s hardly necessary to remind CB&B readers that Prohibition proved devastating to quality beer and the beer business by producing sixty subsequent years of consolidated, industrial-scale brewing. The tightly defined gender roles of the ’50s and Mad Men-era marketers created an image of beer as a drink for men, made by commercial breweries where women were valued only as promotional vehicles. But what may prove surprising is that even after Prohibition, women never ceased brewing. Not entirely, anyway.

“In northern Vermont they were constantly homebrewing in the late ’60s and early ’70s—both men and women,” Smith says. “It had never stopped.” The same can be said for primitive parts of South America, Africa, and the Far East, where women still brew for their communities using the techniques of their maternal ancestors. In some Peruvian, Japanese, and Taiwanese tribes, twenty-first century brewsters chew rice to release fermentable starches. Women in Burkina Faso (West Africa) mash and ferment sorghum beer in facilities that resemble those in place 5,500 years ago, and groups of Chinese and Cambodian women continue to slurp beer through straws. And as contemporary Western women lace up their pink boots and chew their way back into brewing, McGovern predicts that a world’s worth of discovery lies ahead.

Says the biomolecular archeologist who officially concluded that the samples from Jiahu and Godin Tepe had safeguarded humanity’s oldest links to beer: “Women are so often tied, through art and other ways, to these (ancient) fermented beverages. As we acquire more information, I believe we’ll see that women are more involved than we thought.”

In _“Replanting the Seeds of Brewing,”__ we take this history of women’s contributions to brewing up to present times, spotlighting the women who have helped the modern craft-brewing revolution take root._