No question, people love IPAs. A prime reason is that they are supreme showcases for the heady aromatics of hops: resin, pine, herbs, citrus, stone fruit, tropical fruit, and more. As most of this vocabulary describes food, a question arises: If these food flavors are so delicious in IPAs, why don’t we just add them directly? Despite some purists out there, many brewers have done exactly that.

Adding “other” things to beer besides the Reinheitsgebot trio of malt, hops, and water is a practice that must be as old as beer itself. In most places, for centuries, brewers have used any and every handy thing to add flavor and satisfy local tastes. Fruit would either spike the alcohol with extra fermentable sugars or add seasonal, local flavors. Spices were widespread early on; hops didn’t make it to the brewery until about A.D. 900. Today, spices are traditional in some Belgian beers and a tool of creative craft brewers the world over. Wood can act as a sort of spice, too. Until the end of the 19th century, contact with wood was the norm because there wasn’t much else to put beer into.

Adding fruits and seasonings to IPA, however, is new. This market trend started about 2010 with citrus versions. Being so driven by hop flavors, IPAs offer both challenges and opportunities for creative brewers—but whatever they decide to brew with, it has to play nice with the hops. Fortunately, the flavor chemistry of hops offers bountiful possibilities.

Deconstructing the Desired Aromas

Hops are one of the most aromatically complex botanicals that we know, with hundreds of different compounds responsible for their attractive bouquet. They get a lot of their floral, citrus, pine, and herbal aromas from hydrocarbons called terpenoids. Amazingly widespread across the plant kingdom, the terpenoids in hops also occur in a huge range of herbs, spices, flowers, and fruit—especially citrus fruit. The Good Scents Company database (a really cool resource on aroma chemicals) shows more than 200 natural sources for linalool alone.

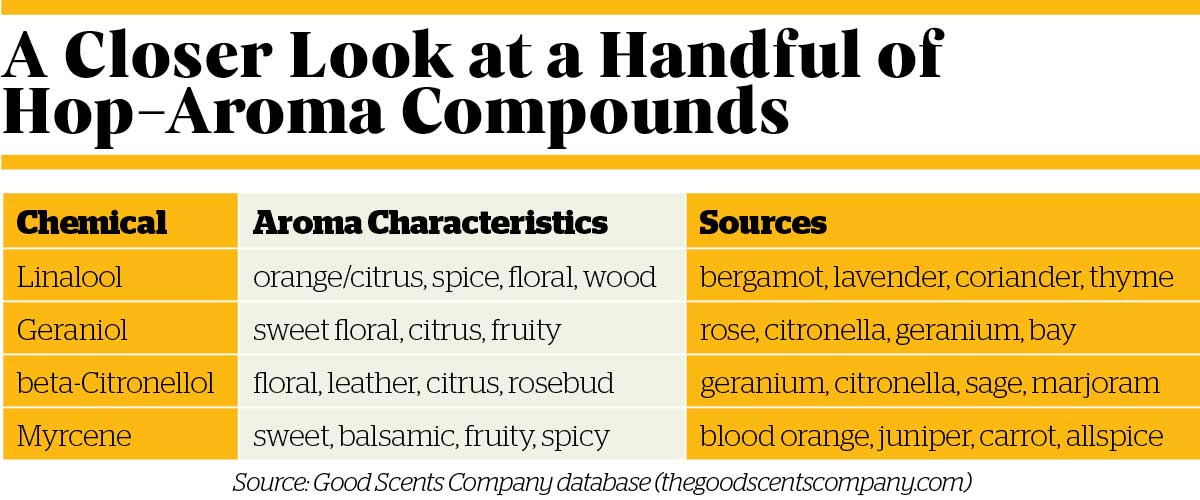

Each hop variety has a specific mix of aroma chemicals, with a pecking order of desirability in today’s marketplace (see table below for a handful of hop-aroma compounds). Geraniol provides the classic, pungent, floral aroma of Cascade and its “C-hop” cousins—and while that aroma is beloved, the market has moved on. Linalool, with its orangey/coriander character, is often see as more desirable, while the lemongrass notes of beta-Citronellol get people excited these days.

Hops—especially the newer tropical- and fruit-forward varieties—are lower in some of the less desirable terpenoids. They also contain small amounts of potent sulfur-containing compounds called thiols, blessed with bright tropical notes: mango, passion fruit, guava, grapefruit, pineapple. These have long, hyphenated names and are usually identified with just their acronyms: 3M4MP (grapefruit), 4MMP (black currant, tropical), 3MH (guava, tropical), and 3MHA (muscat, passion fruit).

Reconstructing—with Fruit

Citrus-spiked IPAs are the most widespread and popular—and the most obvious natural extension of hop flavors. New Belgium had a pretty good hit with their Citradelic (tangerine) as did Ballast Point with their Grapefruit Sculpin. Many breweries are currently using common as well as more exotic citrus such as yuzu and bergamot, both of which share linalool and other terpenoids with hops.

Any beer with specialty ingredients is a challenge. As Elysian Brewing Founder Dick Cantwell says, if you overdo things, you’ll end up with “Grandma’s IPA”—that is, a little too much of everything, layered on randomly. Flavors need to be harmonious and properly balanced and to tell a single story. Flavor notes that stick out can be distracting or even disrupting. Like blue notes, it’s okay to have them, but you have to choose carefully. The added ingredients have to partner with the hop flavors already there and nudge them in some new direction—but push too far, and you’re out of the style expectations. Also, some hop aromas can mask or fight others. Geraniol-rich Cascade and related varieties can be domineering and may dull bright fruity or citrusy notes. Like jazz, it’s sometimes the notes you don’t play that matter as much as the ones you do.

Citrus—including lemons, various oranges, mandarins, and tangerines—are very reliable in terms of delivering their flavor into the finished beer. Sour/bitter/Seville oranges are the classic for Belgian witbier and other historic styles. Lime and especially grapefruit can be a little more reticent to show their true character.

You can add citrus peels to the whirlpool or after fermentation along with the dry hops, adding aroma and nothing else, with no acidity altering the balance of the beer, and no sugar needing to be fermented out. The zest is preferred, as the white pith can add a harsh, tannic bitterness that can detract. Although historic beers often use dried peel, citrus oils can oxidize into a furniture-polish character, so fresh or frozen zest is usually a better choice.

Non-citrus fruit IPAs are out there, along with an acidic sub-style typically employing a combination of kettle souring and the fruit’s natural acidity. Yellow fruits, especially tropical ones, are more harmonious with the hops in IPAs than red ones such as cherry or raspberry. Mango, guava, and passion fruit are expensive, but they are tasty and hop-friendly—no wonder they’re the favorites. Pineapple is delicious, but its subtle flavor demands a lot of puree or juice for a great experience.

One challenge for fruit beers is that peoples’ fruit experience is based on 100 percent fruit or juice, while the brewer is trying to re-create that flavor with perhaps 10 percent juice or puree—a tall order. Adding acidity is helpful except with super-sour fruits such as passion fruit. No clear line separates IPA from non-IPA, but if you add acidity and lower the bitterness, at some point it loses the balance of an IPA and becomes something different, no matter what you call it. A little sweetness may also be helpful, either via mashing techniques or with added lactose, as is sometimes seen in sour fruited IPAs. A dab of vanilla can do the same, but it turns the fruit into more of a confection.

Fruit juices, purees and concentrates contain fermentable sugars. They are best added toward the end of fermentation, as residual sugars in packaged beer can cause over-pressurized kegs and exploding cans. Some fruits are notoriously unstable in beer. Peaches and their kin are especially challenging because their main aroma compound, gamma-decalactone, seems to vanish during even a short fermentation. As a fix, it’s often replaced by a little “top-note” aroma extract, helping achieve a ripe natural flavor that can be challenging with pure, real fruit alone.

Photo: Jamie Bogner.

Reconstructing—with Other Botanicals

Herbs and spices also have a huge overlap with hop-aroma chemistry; many can be superbly harmonious in IPAs. Used judiciously, culinary herbs such as rosemary and thyme can add subtle aromas without getting into pizza territory. Juniper would be perfect—except that its resiny aroma compounds are nearly insoluble in beer’s watery, low-alcohol mix. One early herbal IPA success was Cantwell’s Elysian Avatar Jasmine IPA, which brought together jasmine’s perfumey, grape-jelly, wild-beast personas while clinging to its IPA-ness.

Spruce tips, although hard to source, make great IPAs. Rather than smelling of evergreens, they’re fruity/resiny, perhaps a bit like fresh fig or plum. Geoff Larson, founder of Alaskan Brewing, has long been fascinated with pioneers’ and native peoples’ use of spruce tips as a spring tonic rich in vitamin C. Alaskan Winter Ale was the original, but more recently they added a Spruce IPA.

Coriander isn’t much use in IPA unless you want to add even more linalool, as the stuff is loaded with it. However, sage, basil, ginger, cardamom, bay, woodruff, lemongrass, grains of paradise, and pink peppercorns all have their charms—alone, in combination with each other, or with fruits. Many florals make great seasonings: chamomile brings a little Juicy Fruit; orange blossom glows with an ethereal, ripe citrus; heather is fruity and balsamic; hibiscus is tart and softly tannic (and begs a philosophical question: can it still be an IPA if it’s pink?).

Oak chips, when added early in fermentation, can morph into subtle vanilla and add an appealing lushness in hazy/juicy styles, with crisp tannins tightening up the finish. Brazilian craft brewers are rightfully fond of woods traditionally used for cachaça (sugarcane rum) aging, such as amburana with its complex cinnamon/sassafras character.

In the end, the artful use of “abnormal” ingredients is a great way to expand the delicious universe of IPA possibilities, taking the adventurous drinker where no hop has dared to travel before.