Were you to present a taster tray to a craft-beer newcomer and ask your subject to identify the pale ale in the lineup, he or she could be forgiven for pointing to the Pilsner. The pale in pale ale is a holdover from a time when most British pints were opaque (see How Pale is Pale? below), while today’s pale ales are almost universally a translucent copper hue, somewhere between blonde ale and amber.

The name might not be as apt an appellation as it once was, but pale ale is more relevant than ever. Walk into any pub in Britain and you’re virtually guaranteed a pint of bitter, lovingly pumped up from the cellar with a swan-necked beer engine. And American pale ale lies at the very heart of the Hophead Revolution, offering a blank canvas upon which to slather hops even while retaining enough malt backbone to remind you that it isn’t an IPA.

Pale ale’s appeal lies in its ability to invite endless experimentation while remaining an intimately familiar everyday ale. When your palate can’t take another sour and your liver has had it with imperial stout, pale ale is the old friend you keep coming back to again and again.

From Whence It Came

Once upon a time, all beer was dark and smoky thanks to rudimentary malt kilning techniques that involved wood fire and offered brewers little control over the drying process. As technology improved, malts became increasingly lighter in color, culminating in the so-called white malt that brewers in Burton-on-Trent favored in the 1800s. So popular was this extra pale malt that Czech brewers stole the idea and invented what we now know as Pilsner malt.

Armed with this new pale malt, British brewers exported vast quantities of pale ale to India before it began catching on in Britain as a refreshing alternative to various brown and black beers. Thus, pale ale as a distinct style emerged initially as “pale ale for India” and later as the diverse family of English bitters whose starting gravities were eventually driven southward by taxes and wartime rationing.

English Pale Ale

English pale ales are affable and approachable. Also known as bitter, English pale ale is a single continuum of beer styles (more on that in a bit), with some examples barely breaching 3 percent alcohol by volume ABV) and others climbing to 6 percent ABV or higher. These beers also tend to have wonderfully evocative names such as Workie Ticket (Mordue Brewery), Old Hooky (Hook Norton Brewery), Big Lamp Bitter (Big Lamp Brewery), and Old Speckled Hen (Greene King Brewery).

Built on a foundation of nutty, biscuity British pale malt, English pale ales almost invariably feature a healthy measure of crystal malt, which adds caramel or toffee-like depth. Some examples also include a bit of toasted or roasted malt, more for color than flavor, and others even sneak in maize or sugar adjuncts from time to time.

In English pale ales, hops are almost always of English origin. Floral, earthy East Kent Goldings hops are perhaps most closely associated with English pale ale, but minty, grassy Fuggle comes in a close second. Styrian Goldings from Slovenia also find their way into these beers, but Styrians are biologically Fuggles, not Goldings. Common bittering hops include Challenger, Northdown, and Target.

A defining feature of English pale ale is a recognizable complement of fruity esters that derive from the signature yeast strains that ferment these ales. As a general rule, English strains are moderate attenuators and highly flocculent, which means that English pale ale tends to be brilliantly clear and full-bodied. It is this fullness on the palate that makes even low-gravity examples sturdy enough to prop up a night of larking about.

English pale ales are usually at their best when served in the traditional way, which is with low carbonation (1.1–1.5 volumes, or 2–3 grams per liter, of CO2) and at cellar temperature (50–55°F/10–13°C). When English pale ale first came on the scene, pub customers commonly requested pints of bitter to distinguish such ales from sweeter, maltier mild ales. The name stuck, and nowadays, the term bitter typically implies a cask-conditioned draft product that one purchases in a pub, while pale ale means a bottled beer meant to be consumed off premises.

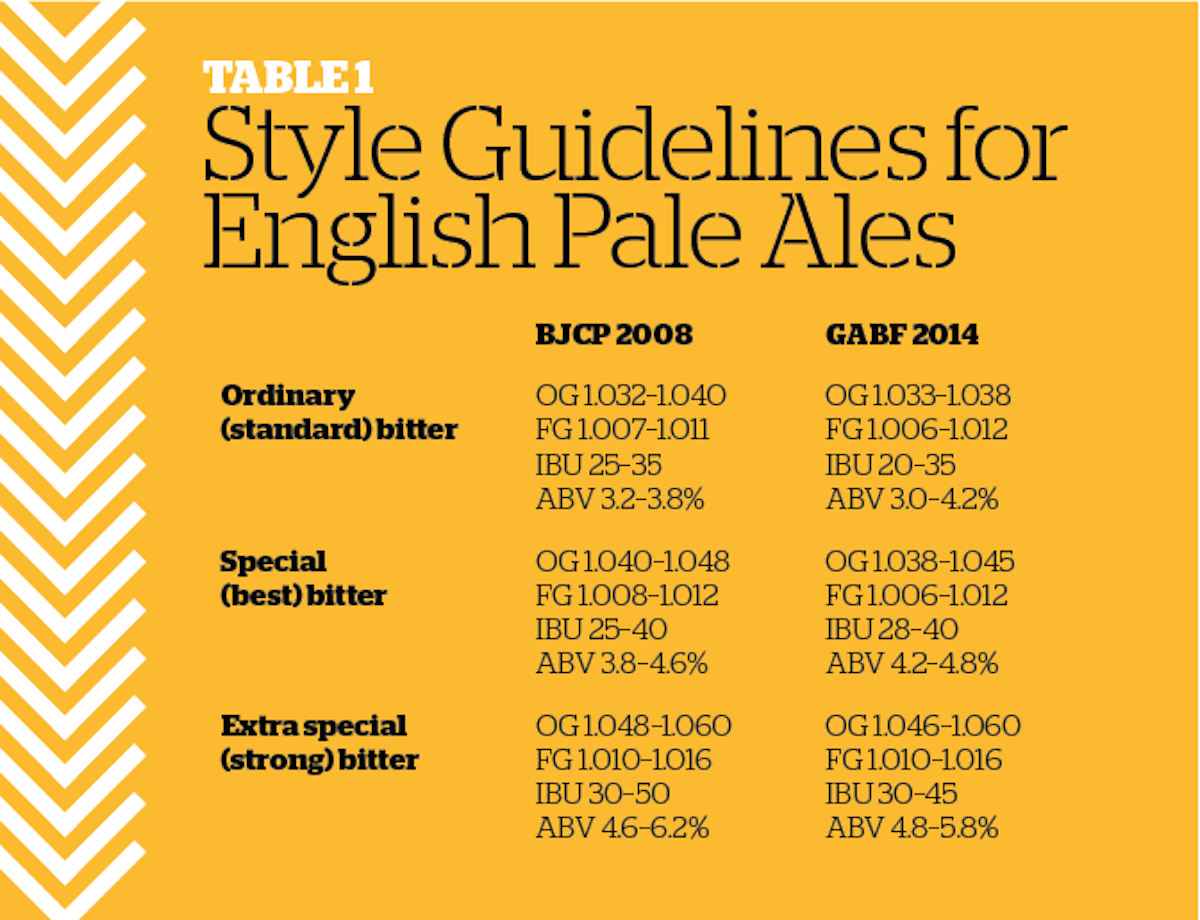

Finally, a note on nomenclature. Bitter, ordinary bitter, special bitter, best bitter, and extra special bitter (ESB) are all English pale ales: They differ only in their relative strengths. The Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) 2008 and Great American Beer Festival (GABF) 2014 style guides divide English pale ale into three completely arbitrary categories, shown in the table below.

American Pale Ale

The pioneers of American craft brewing initially followed British brewing traditions because the equipment requirements are relatively simple, and much of the early homebrewing literature came from the United Kingdom. But, as is usually the case, American craft-brewed pale ale soon broke ranks from traditional English bitters and charted its own course, which, naturally, includes more hops.

The archetypal American pale ale (APA) is that brewed by Sierra Nevada Brewing Company (Chico, California), which is usually credited as having invented the style. What originally set Sierra Nevada’s interpretation apart was its reliance on the then-boisterous Cascade hops, with its signature grapefruit-like aroma and flavor. This paved the way for countless others, including Mirror Pond from Deschutes (Bend, Oregon), Zombie Dust from Three Floyds (Munster, Indiana), AlesSmith X (San Diego, California), Victory Headwaters (Downington, Pennsylvania), Firestone Walker’s Pale 31 (Paso Robles, California), and Dale’s Pale Ale from Oskar Blues (Lyons, Colorado).

While English pale ales remain fairly balanced between malt and hops, American pale ales definitely lean toward the latter. The malt backbone of American pale ale is mostly there to balance the hops, although care should be taken not to be too restrained with the malt, lest one end up in IPA territory. The typical grist for an American pale ale is built on American pale malt or 2-row, with varying amounts of caramel malt. Some brewers like to include a portion of Munich or Vienna malt to fortify the background malt character, but this is by no means universal.

As with most American derivatives of English styles, hops play a greater role in American pale ale than they do in the British original, but it’s not just about quantity: It’s even more a question of aroma and flavor. While English pale ales display floral, earthy, and even grassy hops aromas and flavors, American brewers prefer to infuse their pale ales with citrus, pine, resin, and tropical fruit. Typical hops varieties found in American pale ales include old classics such as Cascade, Centennial, Columbus, and Chinook; proprietary examples such as Amarillo, Ahtanum, Citra, Simcoe, and Mosaic; and, increasingly, hops from Down Under such as Pacifica, Rakau, Motueka, and Galaxy.

Another distinguishing characteristic of American pale ale has to do with the timing of hops additions. While English bitters usually rely on a single bittering charge and a moderate flavor and aroma dose toward the end of the boil, late hopping is essential to American examples of this style. Virtually all American pale ales feature a generous addition of hops within the last few minutes of the boil; most receive some kind of addition at flameout; and many are even dry hopped. This late hops character makes American pale ale so intoxicating.

American pale ales usually exhibit restrained yeast character. A few subtle esters are there, enough to let you know you’re not drinking a lager, but the overall impression is clean enough that one’s focus remains on the brewer’s expression of malt and hops. In fact, the most popular APA yeast strain for homebrewers and professionals alike is the so-called Chico strain, said to have originated with Sierra Nevada and sold commercially as Wyeast 1056 American Ale, White Labs WLP001 California Ale, and Fermentis Safale US-05.

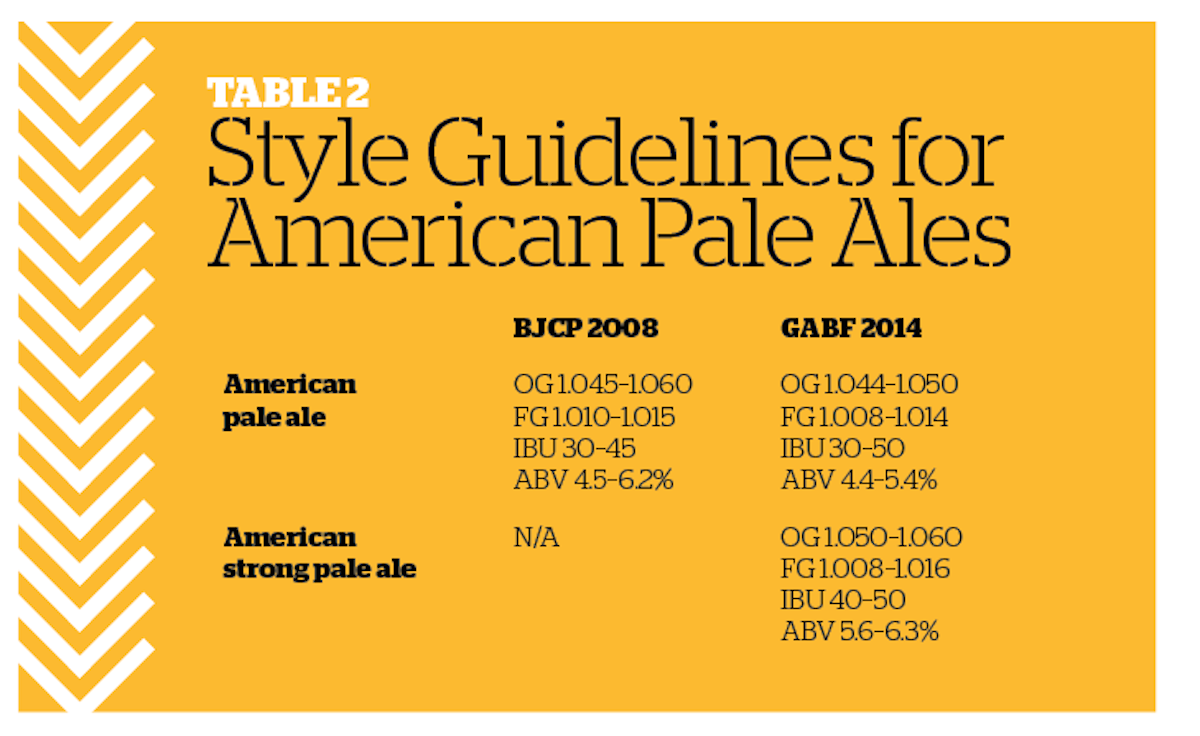

As shown in the table below, the BJCP’s 2008 style guide recognizes one American pale ale (IPA notwithstanding), while the GABF 2014 guidelines describe two.

Belgian Pale Ale

While one usually thinks of England and the United States when speaking of pale ale, the Belgians also produce the aptly named Belgian pale ale. Built on European Pilsner malt, Belgian pale ale is a delight, balancing up-front malt sweetness with toasty whole-wheat cracker-like overtones and just enough hops bitterness to keep everything in check. A Belgian yeast strain usually offers up a bit more in the way of esters than is found in American pale ale, but fermentation by-products aren’t nearly as intense as those that typify dubbels, tripels, and Belgian strong ales.

Commercial examples of Belgian pale ale include De Koninck (Antwerp, Belgium), Rare Vos from Brewery Ommegang (Cooperstown, New York), and New Belgium Brewing’s Fat Tire (Fort Collins, Colorado/Asheville, North Carolina), which may be marketed as an amber ale, but stylistically, it’s a Belgian pale ale.

Whether you’re enjoying a nonic pint of bitter in Leeds, a shaker glass of APA in Portland, or a bolleke of biscuity Belgian beer in Antwerp, there’s a pale ale for every occasion. As comfortable with a bowl of steamed mussels as it is with cold leftover pizza, it’s the ultimate everyday beer that makes others pale in comparison.

How Pale Is Pale?

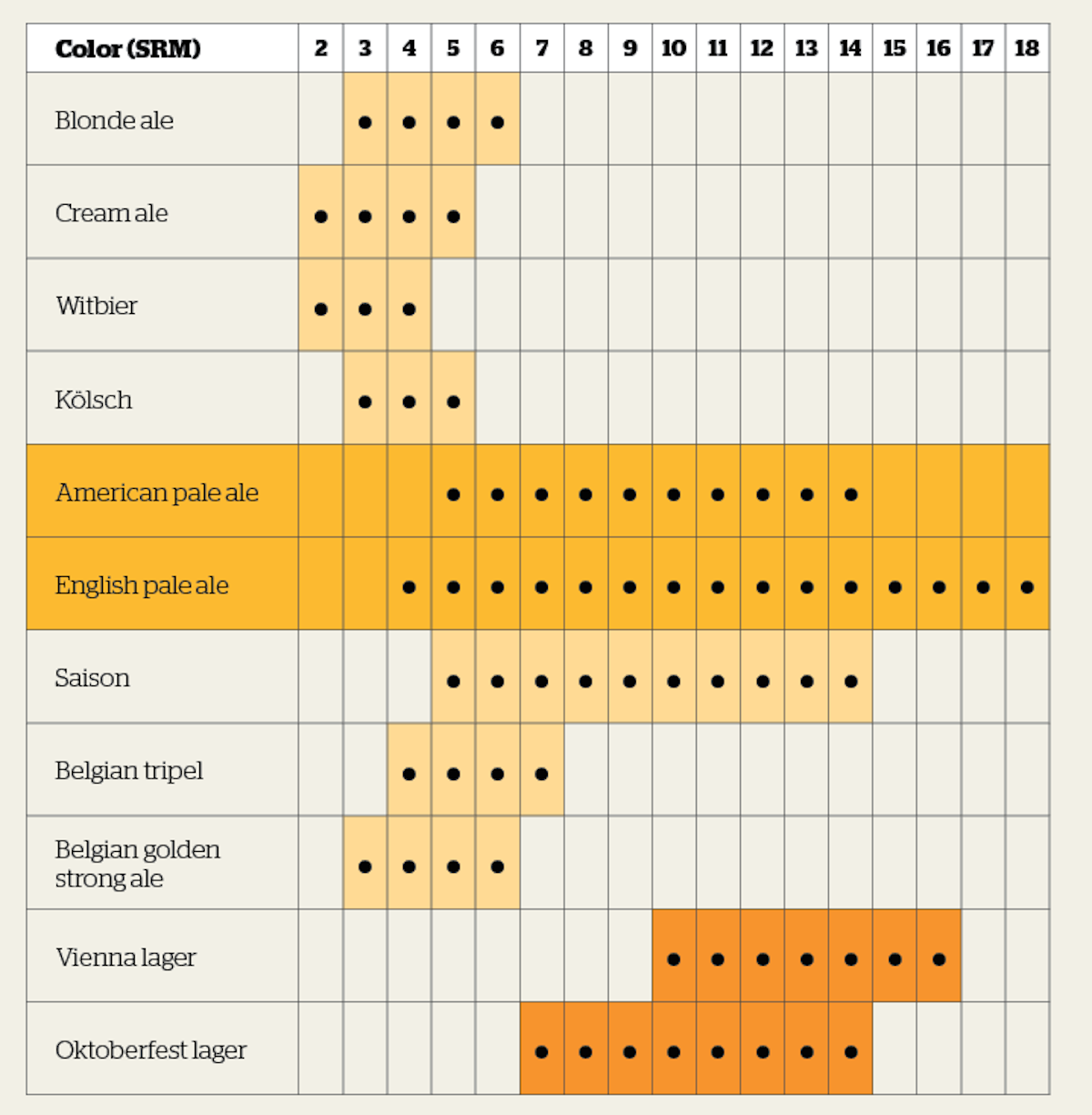

When is pale not pale? When it refers to pale ale, of course! Below are some color ranges for a few selected styles, as suggested by the Beer Judge Certification Program’s (BJCP) 2008 guidelines. Not only are English and American pale ales generally several shades darker than blonde ale, cream ale, wit, and Kölsch, but they are often as dark as Vienna and Oktoberfest, both considered amber lagers.

It all comes down to context. Pale ale is, in fact, pale, but only in comparison to mild ales, brown ales, porters, and stouts. As I explain above, until pale malt became widely available, beer would have necessarily been some shade of brown or black. The term pale ale was coined when improved kilning technology enabled brewers to create ever-lighter malts, which led to ever-lighter beers. Compared to the porters of yore, the new beers were very pale, indeed.

But still today, the term can remain a bit of a stretch, even within the style category itself. Apparently different brewers have different ideas of what it means to be pale. Here are the approximate SRM values of a few commercial examples:

- Firestone Walker Pale 31 — 7 SRM

- Mirror Pond Pale Ale — 9 SRM

- Sierra Nevada Pale Ale — 10 SRM

- Fort Collins Brewery 1020 Pale Ale — 12 SRM

- Firestone Walker DBA — 13.5 SRM

- Schlafly Pale Ale — 13.5 SRM

- Ska Brewing Euphoria Pale Ale — 15 SRM

All of this is, of course, fairly inconsequential, particularly in light of such category-defying terms as black IPA and golden stout. As far as I’m concerned, you can call your beer whatever you like, as long as it tastes good!