Ingredients: The Four Pillars of Great Beer

Malt is the soul, hops the spice, yeast the spirit, and water the body of beer. —Prof. Dr. Anton Piendl, Weihenstephan Brewing Science and Beverage Technology Program, Technical University of Munich

The most important part of making good beer is to fully clean and sanitize all of your equipment. The second most important part of making good beer is to understand, and always use, fresh high-quality ingredients. Know your raw materials, and you’ll forever have the upper hand when you brew.

Beer is traditionally brewed from just four ingredients:

Keep in mind that these are merely the building blocks. Beer can also include spices, fruits, juices, chiles, coffee, purees, a variety of sugars, two turtle doves, and a partridge in a pear tree. In the past year, I’ve tried—and, for the most part, enjoyed—beers that have included basil, cucumbers, peanut butter, and even cinnamon rolls. If it’s out there, there’s a good chance someone has tried to ferment it (some attempts, of course, turn out better than others).

It’s fun to play with exotic ingredients, but for now, let’s focus on understanding the four fundamental ingredients that comprise, at least in part, every beer you’re likely to ever brew.

Malt: The Soul of Beer

Malt is to beer as grapes are to wine, as honey is to mead, and as apples are to cider. It supplies the sugars that yeast cells convert into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Without malt, beer as we know it would not be. It is as fundamental to ale and lager as rice and maize are to the great cuisines of Asia and Mesoamerica.

Malt is available in a dizzying number of forms, and the first time you walk into your neighborhood homebrew store, you might feel overwhelmed by the vast selection. Malts often look more or less identical and have similar sounding names, so how are you to know what’s what?

As complex as malt can be, knowing how to work with it as a homebrewer really means understanding just two things:

- Malt is always made from a *cereal grain* (such as barley, wheat, rye, or oats) that has been modified to make its internal starches readily available for brewing. The degree to which a malt is modified from raw grain is called—wait for it—modification.

- Malt is always kilned (heated) to some degree. The degree of kilning may be so light as to be virtually unnoticeable or so aggressive that the kernels turn completely black. But it’s always there. The degree to which malt is kilned is called kilning (maltsters are an imaginative lot).

That’s it. Modification and kilning are the two processes that transform raw cereal grains into malt. Keep this in mind and everything else is just a matter of degree. That said, let’s now take a closer look at the soul of beer.

Malt Basics

Malt is nothing more than a seed that has been tricked into thinking it is about to sprout into a new plant and then abruptly denied the opportunity to do so.

Think back to when you were in science class in grade school. Remember when you took, say, a kidney bean, placed it in a little water on the windowsill, and watched it sprout? That’s really all that malt is, except you halt the process before the sprout has a chance to get too big.

Why is this important? Well, think about what a seed is. It’s a small self-contained botanical package that has everything a new plant needs to kickstart its growth and develop into a seedling. Once that seedling sprouts leaves, it can make its own food using photosynthesis. Until that point, though, it needs to rely on its internal food stores.

Those internal stores are packaged as starches, which are very long chains of sugars. Chew on a cracker (which is mostly starch) for a minute or so, and once you get past the disgustingly mushy texture, you’ll start to notice that it tastes sweet. That’s because our saliva contains enzymes, which decompose starches into their constituent sugars, a process that continues when food reaches the stomach. (In fact, there’s a drink indigenous to the Andes called chicha, which is traditionally made by chewing on maize/corn, letting the salivary enzymes do their work, and spitting the resulting mush into a pot. Get the whole village together to chew and spit for a few days, and pretty soon you have enough to ferment a beverage, which only further demonstrates the universal truth of Brillat-Savarin’s assertion from the Introduction.)

Just like your saliva, kernels of barley, wheat, rye, oats, and other cereal grains also contain enzymes. And it is precisely these enzymes that allow a seed to start growing by deconstructing complex starches into simple sugars that it can use. Storing energy as starch is much more efficient and compact than storing it as sugar, so Mother Nature packs seeds full of starch as well as enzymes that the growing plant needs to convert the starch to sugar.

Yeast, the miracle fungus that makes all alcoholic beverages possible, cannot consume starch. But it has virtually no self-control when it comes to sugar. Thus, brewers exploit the natural enzymes within barley, wheat, rye, and other grains to degrade the starches in those grains into sugars that yeast cells can readily devour. For those enzymes and starches to become available, though, the seed needs to sprout, and then something has to stop it. That is where malting comes in.

A maltster first soaks raw grain in water and holds it at a specific temperature. Warm, moist conditions prompt the grain to initiate the germination process, and eventually small rootlets, called chits, emerge from each kernel. Simultaneously, a young shoot, called the acrospire, develops within the kernel itself and grows in the opposite direction of the chit. All the while, enzymes are activating and preparing to convert the seed’s starches into sugars to nourish the developing plant. This process of transforming a raw seed into a starch- and enzyme-rich malt is modification.

Eventually the malt reaches a stage of maturity at which the enzymes are fully developed. It is at this point that the malster increases the temperature and begins kilning the malt. Heat stops germination in its tracks and locks the malt into a sort of state of frozen animation. Depending upon the type of malt being produced, kilning may be a quick affair that does little more than shut down germination, or it may proceed to an advanced stage that renders the malt black (and there are many intermediate stopping points as well). After the malt has been modified and kilned, it is bagged and sent off to professional brewers and homebrewers alike.

When malt reaches the brewhouse, it’s ready to be used in a process called mashing. A mash is a thick, porridge-like mixture of crushed malt and hot water. The hot water hydrates the malt’s starches and brings to life the enzymes that the maltster so carefully made available. Over a period of time, those enzymes break down the grain starches into simple sugars, which yeasts will eventually consume and create carbon dioxide (bubbles) and alcohol (booze).

Malting and mashing actually represent two steps along a single continuum, and there’s no technical reason why breweries can’t do both. In fact, the very largest breweries in the world actually do operate their own malting facilities to produce malts that meet the exact specifications of the brewers who will work with the malts.

But most breweries—and certainly most homebrewers—don’t bother with the malting part. Instead, we purchase ready-made malt that has been produced in a malt house, or maltings, as it is sometimes called. And it is this malt that you need to decipher when designing a recipe or purchasing ingredients.

Types of Malt

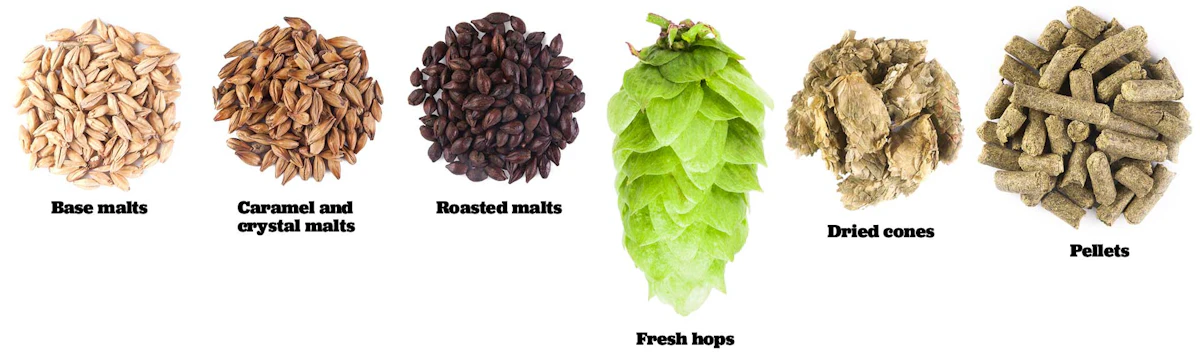

Malt generally falls into two broad categories: base malt and everything else. That everything else, usually called specialty malt, is further categorized into caramel/crystal and roasted malts, so a good taxonomy for the types of malts you’re likely to encounter is as follows:

Base malts, which are modified and then very lightly kilned

Caramel and crystal malts, which are modified and then moderately kilned

Roasted malts, which are modified and then heavily kilned

There are a few exceptions, of course, but this organizational scheme captures the vast majority of the malt you’ll come across. In the following sections, you’ll learn a little more about what each of these malt families is good for.

Base Malts

Every beer contains at least one kind of base malt. Base malt is so named because it forms the base upon which a recipe is built. Supplying the bulk of a beer’s fermentable sugars, this class of malts usually represent anywhere from 75 to 100 percent of the grain that goes into a recipe.

A base malt’s influence can range from style-defining to barely noticeable. A classic Bohemian Pilsner such as Pilsner Urquell (Czech Republic), for example, relies exclusively on Moravian Pilsner malt to achieve the delicate golden base upon which spicy Saaz hops are slathered. An intense barrel-aged imperial stout such as Goose Island’s Bourbon County Brand Stout (Chicago, Illinois), however, includes so many specialty malts and so much barrel-aged character, that it’s hard to pick out the base malt that lies beneath all that complexity.

Base malts come in all kinds of varieties, but the most important thing to know is that base malts contain enough enzymes to fully convert their own starches into sugars, and—in many cases—they have extra enzymes to convert starches in other grains as well.

Common base malts include

- Pilsner malt, which is sometimes called Pils malt. This is the lightest malt available. Pils malt forms the base for the vast majority of lager styles.

- Pale malt, which is often called, simply, “2-row.” It’s usually a shade darker than Pils malt, though not by much. Pale malt forms the base of the majority of ale styles.

- Pale-ale malt, sometimes referred to by its specific cultivar, such as Maris Otter or Golden Promise. These tend to lend a slight nuttiness or more rounded malt flavor to beer.

- Munich malt, which comes in varying degrees of color. These are more highly kilned than Pils and pale malts, but they still act more like base malts than caramel or crystal malts. Munich malt is traditionally found in dark German lagers such as Bock and Oktoberfest/Märzen, but it has become popular for a wide range of styles.

- Vienna malt, which is very similar to Munich malt. It forms the basis for traditional Vienna lager.

- Wheat malt, which contains no husk and is almost always used in conjunction with barley malt. German wheat beer traditionally includes more than 50 percent wheat malt, with Pils malt supplying the balance.

- Rye malt, which has similar properties to wheat malt and delivers a signature spiciness not unlike rye bread. Rye malt is typically used in small quantities, up to about 20 percent.

Further complicating base malts is the fact that they come from North America, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Czech Republic, and elsewhere. Each growing region contributes its own unique terroir, which means that Pilsner malts from Germany and the United States are likely to have a rather different taste and brewhouse performance.

Caramel and Crystal Malts

Beer brewed from just one base malt can be very good. Classics such as Pilsner Urquell (Czech Republic) and Timothy Taylor’s Landlord (United Kingdom) contain nothing but Pilsner malt and Golden Promise malt, respectively. But most styles, from red ales to Doppelbocks, need additional supporting malts to add flavor, color, aroma, and body. That’s where specialty malts come in. These are malts that have undergone additional processing to change their flavor and aroma.

Caramel and crystal malts usually have a glassy appearance (hence, “crystal”), and including them in a recipe lends caramelized flavors and aromas to your beer. When you sample a beer and pick up notes of toffee, caramel, raisins, or plums, there’s a very good chance that you are tasting the influence of caramel malt.

Caramel and crystal malts are produced by heating hydrated, modified grain at various temperatures for various lengths of time, depending on the product being made. The simultaneous influence of moisture and heat stews the malt’s starch right inside the husk, converting starch to sugar just like a little mash. The process also creates Maillard reactions, which are the same chemical phenomena that cause meat to brown when cooked in a hot skillet.

Common crystal and caramel malts include

- Dextrin malts such as Carapils® and Carafoam®

- Crystal malts numbered roughly 10–150 (the higher the number, the darker the color)

- Caramunich malt

- Honey malt

- Melanoidin malt

- Special B® malt

One confusing aspect of these kinds of malts is that every manufacturer tends to name its products using trademarks that are only slightly different from one another, often involving some riff on the word caramel or the prefix cara-. Thus, you’ll find Carapils®, Carafoam®, Caramunich®, Carastan®, and so on. Fortunately, any maltster worth dealing with will also provide a numeric rating of the malt’s color, which lets you roughly compare crystal and caramel malts from different manufacturers.

Special B®, for example, is an intense caramel malt from Dingemans Maltings of Belgium. It is about the same color as Extra Dark Crystal, which is produced by Simpsons Maltings in the United Kingdom. However, differences in the base malt used to produce these two products, as well as differences in malting and kilning processes, mean that substituting one for the other is very likely to yield different results in the finished beer. The beer probably won’t be bad, but it won’t be the same.

Roasted Malts

Roasted malts take kilning a step further. The maltster continues to kiln the malt until it starts to take on darker characteristics, not just in color, but in flavor and aroma as well. Chocolate malt, for example, has no chocolate whatsoever in it, but its taste is similar to that of dark chocolate. Black malt is even darker and is the malt equivalent of a French roast coffee: The roast dominates, leaving little of the grain’s original character intact.

Examples of roasted malts include

- Chocolate malt

- Black malt (sometimes called black patent malt)

- Various dehusked roasted malts such as Carafa Special

Roasted barley is usually grouped in with roasted malts, but it isn’t actually malted. Roasted barley is raw barley that has been roasted just like coffee. It’s the signature specialty malt in dry Irish stouts such as Guinness, Murphy’s, Beamish, and O’Hara’s. It has the remarkable property of making a beer very dark without affecting the head at all, a visual trick that is at its finest in a freshly poured Guinness Draught from a nitrogen-powered stout faucet.

Other Malts

Naturally, there are a few kinds of malt that don’t fall neatly into base, caramel/crystal, or roasted malt categories. A few that you may run across include

- Biscuit and Victory® malts, which are base malts that have been specially processed to deliver a toasty, biscuit-like flavor and aroma.

- Coffee malt, which is a roasted malt that offers up a dark color and rich flavor similar to coffee.

- Smoked malt, which has been exposed to wood smoke and has a pronounced campfire- or bacon-like smoke character. Peated malt is similar but has been smoked over peat instead of wood.

Maltsters develop new malts every year, so it’s futile to try naming them all here. A good homebrew retailer should be able to answer any questions you have about malt.

Malt Extract

Malt extract is a convenient malt product that lets homebrewers brew beer without having to mash grain (many professional brewers admit to sneaking a bit of it in from time to time as well). Mashing is neither difficult nor complicated, but it does introduce opportunities for things to go wrong, and it takes time. A typical brew day that starts with a mash might last 5 to 7 hours, but you can easily brew beer from malt extract in just a couple of hours.

So what is malt extract? It’s what you get when you mash a bunch of malt and then remove most of the water. Malting companies mash grain just as one would when preparing to make beer, but instead of adding hops and fermenting the resulting wort, they process the wort to remove water. The result is a concentrated wort that brewers can reconstitute at their own convenience to make beer, just as you’d add water to a can of condensed soup. Malt extract is available in two forms: liquid and dry.

Liquid malt extract (LME) is more meaningfully—but less commonly—described as malt extract syrup. It has a honey-like consistency and could easily fill in for the titular character starring opposite Steve McQueen in 1958’s The Blob. Your local homebrew store is likely to have big plastic barrels of the stuff: All you have to do is tell them how much you need, and they’ll fill a pail for you to take home and brew with. Mail-order retailers usually sell liquid extract in plastic jugs or vacuum-sealed bags.

Dry malt extract (DME), sometimes called spray malt, is made by spraying wort into a warm vacuum chamber. As each little droplet of wort flies through the chamber, the water is almost instantly sucked out of it, and the resulting pile of dry malt compounds is bagged and shipped to homebrewers worldwide. Homebrew stores are likely to sell dry malt extract in plastic bags, usually by the pound or kilogram.

Liquid and dry malt extracts are effectively interchangeable, but because the dry product contains less moisture, you need less of it by weight than an equivalent amount of liquid extract. Dry extract has a much longer shelf life, but it comes with a slightly higher price tag. Both can make equally good beer, and the choice of one over the other is likely to come down to what your supplier carries and how you plan to use it.

Both kinds of extract are available in a wide range of styles, variously formulated for brewing different kinds of beer.

- Pils (or extra light) extract for light lager, Belgian golden ale, and saison

- Pale (or light) extract for pale ale and IPA

- Wheat extract for Hefeweizen, American wheat ale, saison, and more

- Amber extract for amber ales and lagers

- Munich extract for Continental-style dark lagers

- Rye extract for Roggenbier, rye IPA, and anything else that uses rye

- Dark extract for porters and stouts

A great variety of beer can be brewed by simply steeping some specialty grains in hot water for flavor and aroma and adding one of these extracts as the main source of fermentable sugars. In fact, this is the method we’ll use to brew your first beer.

Adjuncts and Sugars: Not Malt, but Closely Related

Finally, let’s talk just a little bit about adjuncts. In the craft-beer realm, the word adjunct itself is a loaded term that suggests inferiority. In truth, it’s simply a catch-all for any source of fermentable sugar that doesn’t happen to be malt. Most industrial-scale American breweries rely on adjuncts such as corn and rice to lighten the body and increase the alcohol content of their products, which may be one reason that adjuncts have gotten such a bad rap.

Used in the right amounts and for the right reasons, however, adjuncts can deliver characteristics you just can’t get from malt. It is worth noting that many of the world’s most-sought-after commercial craft beers, including the elusive Pliny the Elder and Westvleteren XII, include adjuncts such as simple sugar.

Common adjuncts include

- Unmalted cereal grains such as raw barley, wheat (pictured above), rye, and oats

- Simple sugars such as table sugar, brown sugar, honey, and maple syrup

- Belgian candi sugars and candi syrups

- Invert sugars

- Molasses

- Treacle

There’s nothing wrong with using adjuncts in your beer, as long as you enjoy drinking it!

Hops: The Spice of Beer

Malt supplies a diverse range of flavors, aromas, and color, but its number one purpose is to offer fermentable sugars. Without those sugars, there would be no beer. But hops are different. Perfectly enjoyable malt beverages can be made without them, though they’re rather different from what we know today as beer. In fact, before hops became widespread, brewers in medieval Europe relied upon a mixture of herbs called gruit to lend bitterness and flavor to their ales, typically incorporating yarrow, mugwort, horehound, heather, and other botanicals.

Hops, however, ultimately won over brewers thanks to their intoxicating aromas and flavors and—importantly—their antiseptic properties. Today, hops are as essential to beer as malt, water, and yeast, and only a few styles continue to make use of gruit, mostly historical styles that have been resurrected as part of a broader interest in traditional styles and methods. Finnish sahti, for example, includes juniper berries and juniper branches in its production, but rarely does it feature hops.

Hops Basics

Hops are the cone-shaped flowers of the climbing plant Humulus lupulus, a member of the family Cannabaceae, which also includes species of Cannabis. Harvested twice a year (once in the northern hemisphere and once in the southern), hops must be dried in order to be stored and used year-round. Only so-called “wet hops” or “fresh hops” beers use hops in their unprocessed form.

We look to hops for four essential elements in our beer:

- Preservative qualities

- Bitterness

- Flavor

- Aroma

Bitterness and preservative qualities go hand in hand, for both are related to compounds called alpha acids. Alpha acids are found in hops resins and, when boiled in water, convert to a modified form called iso-alpha acids. Boiling, therefore, is the key to unlocking hops’ ability to bitter and preserve our beer.

The act of boiling, however, also drives away volatile oils that are responsible for the unique flavors and aromas that hops have to offer. Therefore, it is common to divide hops into categories that roughly correspond to the length of time they are boiled.

- Bittering hops are added near the beginning of the boil, which usually lasts around 60 to 90 minutes. These hops contribute mostly bitterness to the finished beer and also help preserve it.

- Flavor hops are added in the final half hour or so of the boil. They still contribute some bitterness, but enough precious oils remain to lend their characteristics to the final product.

- Aroma hops are usually added at the very end of the boil, and in many cases, well after the boil is complete. As the name suggests, these hops deliver the beautiful aromatics that we love to sniff in, say, a freshly poured India Pale Ale (IPA).

In the past, different hops breeds were roughly categorized as bittering, flavor, or aroma hops, but the lines today are much more blurred than they once were. It is now common for a single variety of hops to be used at all points in the production of a beer.

Now let’s consider a few of the forms in which you may find hops at your local homebrew store.

Fresh Cones

Fresh (or “wet”) hops cones are the least processed form of Humulus lupulus you’ll encounter. Available for a very limited time during the autumn harvest (typically late August to early October in the Northern Hemisphere, depending on climate and latitude), fresh cones are best used within 48 hours of being plucked.

The most convenient way to get your hands on fresh hops is to grow them in your own backyard: It’s easier than you think (or so I am told. I hold an enviable record when it comes to successfully destroying otherwise healthy-looking plants, hops included).

If gardening isn’t your thing or isn’t an option, some homebrew stores now organize pre-orders and will overnight fresh hops directly to your door. But you have to be ready to use them when they arrive. Those who live near hops farms may be able to negotiate a few pounds of freshies in exchange for a day of volunteer labor (harvesting hops is hard work!).

However you acquire them, fresh cones are almost always used late in the boil to add aroma, or even after fermentation to infuse the beer with incredible fresh hops aroma. This, of course, requires a bit of timing so that the hops can go straight into the beer after harvest.

Dried Cones

Sometimes called whole cone or leaf hops, dried cones are fresh cones that have been dried so that they can be stored for year-round use. Properly stored, dried hops can last for several years with only minimal degradation. Some breweries pride themselves on brewing only with whole-cone hops and deploy legions of marketing professionals to make sure that consumers know it.

As a homebrewer, you’ll have no trouble finding high-quality dried hops cones. Given their bulk, whole cones do present some storage challenges, though, which is why homebrewers and professionals alike overwhelmingly choose hops pellets.

Pellets

Hops pellets may not be as romantic or as nice to look at as whole cones (they resemble a peculiar cross between rabbit food and, let’s say, Soylent Green?), but what they lack in aesthetic appeal, they more than make up for in convenience. Pellets are just dried cones that have been compressed and extruded through a die to create little pellets. The sticky resins within the hops are sufficient to hold the pellets together, so binding agents are neither necessary nor added.

Pellets offer several advantages over whole cones:

- Because they are compressed, pellets take up much less space than whole hops cones.

- Pellets have a lower ratio of surface area to volume than cones, which makes them less vulnerable to oxidation.

- Pellets tend to have more uniform performance characteristics than cones because the production process averages out variations in the crop.

In the end, choosing pellets or whole cones is less important than ensuring that the hops you purchase are properly stored, which means reducing exposure to oxygen and light as much as possible. Your homebrew retailer should only sell hops that are stored in the dark and that are either vacuum sealed or packaged in an inert gas such as nitrogen. Do not be afraid to ask your homebrew retailer about their hops-storage methods!

Yeast: The Spirit of Beer

The finest barley and hops in the world won’t yield beer as we know it without yeast. This single-celled fungus is responsible for many of the world’s greatest foodstuffs, and were all the world’s yeasts to suddenly go on strike, humankind would find itself without such delicacies as

- Bread

- Kombucha

- Whiskey

- Chocolate

- Salami

- Soy sauce

- Wine

- Sake

- Mead

- Cider

- Vinegar

- Hákarl (Look it up.)

- And yes, beer

When Duke Wilhelm IV of Bavaria issued the famous Reinheitsgebot, or beer purity law, in 1516, the role of yeast was probably recognized, but it certainly wasn’t understood. It took almost 350 years before Louis Pasteur would directly observe and describe how yeast cells anaerobically ferment sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide.

But yeast’s action is far more than mechanical conversion of this to that, and many newcomers to the world of beer are surprised to learn just how much influence yeast has upon the finished product. The signature banana and clove flavors one finds in authentic German Hefeweizen are entirely due to the yeast used. American wheat beers, though similar in other respects, have more neutral profiles because they use yeast strains that we generally describe as “cleaner,” meaning fewer fermentation by-products.

Homebrewers enjoy access to an amazing array of yeast strains. The difficulty in selecting a strain today isn’t finding one that’s up to the task, but narrowing down the many excellent options.

Yeast Basics

Yeasts are single-celled fungi that consume sugars and create alcohol and carbon dioxide. Thousands of unique yeast species have been identified, a number that continues to grow each year. And within each species, countless individual strains have been selectively bred over decades and centuries to perform in certain ways.

The yeasts that you’ll use the most as a homebrewer are of the genus Saccharomyces, which translates from Latin as “sugar eater.” Within this genus, two species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus, are responsible for the vast majority of ales (S. cerevisiae) and lagers (S. pastorianus) enjoyed worldwide. When you hear a brewer or a beer enthusiast talking about yeast without further clarification, in most cases he or she means Saccharomyces.

That said, you may have heard of—or, hopefully, enjoyed—beers that are fermented with so-called wild yeasts. Despite the evocative name, brewers commonly culture and use wild yeasts via the same high-tech methods they use for Saccharomyces. In brewing parlance, the term wild simply means that the microbes haven’t been selectively pressured over the years for desirable brewhouse performance. They’re less predictable—their behavior is a bit, well, wilder. Most commonly, beers are fermented using strains of Brettanomyces, called Brett for short.

Your yeast options come in one of two forms: liquid and dry.

Liquid Yeast

Liquid yeast—or, more accurately, yeast cells suspended in a liquid growth medium—is usually the least processed and most perishable yeast product available to homebrewers. Sold in plastic vials or flexible pouches, liquid yeast offers unparalleled variety and purity. Wyeast Laboratories and White Labs are the two largest suppliers of liquid strains to homebrewers, but smaller companies such as GigaYeast, East Coast Yeast, and The Yeast Bay have started making inroads in the marketplace in recent years.

Purchased fresh, most liquid yeast products supply an optimal population of yeast cells for beers of average strength (stronger beers may require using two or more packets, but we’ll cover that in depth in Chapter 5). The key word here is fresh. Under refrigeration, you can reasonably expect liquid yeasts to remain viable for a few months, but there are many opportunities for improper handling en route from the yeast supplier to your kitchen. For this reason, I always keep a few packets of quality dry yeast on hand just in case my liquid culture fails to take off.

Dry Yeast

Dry yeast is similar to what you purchase in the supermarket when you want to bake bread. It comes in little sachets that typically contain about 11 grams of dry yeast. One sachet of dry yeast has more than enough cells to ferment a typical beer, and because the drying process makes yeast less sensitive to storage conditions, it’s more likely to survive the journey to your house more or less intact. If you mail order your yeast, selecting dry yeast during the warm summer months isn’t a bad idea.

The downside to dry yeast is that, compared to liquid products, far fewer strains are available. The drying process is expensive and time-consuming, so manufacturers only bother drying strains that are popular enough to warrant the effort. Furthermore, some yeast strains simple can’t stand up to the extra bit of processing necessary to dry them. Fortunately, new dry strains are being developed all the time, and it’s now possible to create American ales, English ales, Belgian ales, and German lagers using nothing but dry yeast.

Water: The Body of Beer

Good water is crucial to making good beer, so much so that entire styles have developed to take advantage of the specific water available at different brewing sites around the world. Guinness Draught, Pilsner Urquell, and Bass Ale all owe their existence, at least in part, to the nature of the water in their cities of origin (Dublin, Ireland; Plzeň, Czech Republic; and Burton upon Trent, United Kingdom, respectively).

Water chemistry is a complex topic that warrants far more attention than I can reasonably give it in this book. We’ll touch on water a little in Part III, which explains how to prepare wort using all-grain methods, but a thorough discussion is well beyond the scope of this book. Fortunately, those who brew with extracts don’t need to think too much about their water. Read on to learn why.

Water Basics

Beer is mostly water, so it stands to reason that the water used to brew that beer should be of good quality. But brewers can draw an arbitrary distinction between water quality and water composition.

- Good quality water is free from contaminants and sediment, has a flavor that’s pleasant enough to drink on its own, and is not heavily chlorinated. Most municipal tap water is of good quality.

- Water composition, on the other hand, refers to the relative quantities of dissolved minerals, ions, and salts. It’s what we commonly think of as hard or soft water.

These terms are imprecise and, again, completely arbitrary, but they help us concentrate on what’s important to the brewer. Quality is about potability and taste. Composition is about the specific makeup of the water. That brings us to a very important point:

Water quality is important to all brewers, but water composition is mostly important to those who mash grain.

Water chemistry affects all kinds of reactions in the mash, which is why entire books have been written about it. And yes, those who brew using all-grain methods do need to think about water composition to some degree. But brewers who use malt extract, especially those just getting started, need only consider water quality in most cases. Thus, brewing from extracts boils down to just two basic axioms:

- If your tap water tastes good, brew with it. You should have no problems brewing good beer.

- If your tap water does not taste good (e.g., it tastes minerally, sulfuric, metallic, or otherwise unpleasant), brew with bottled spring water—nothing terribly fancy, just basic drinking water from the local supermarket.

That’s it. Nice and simple. Yes, you may want to tweak things here and there as you gain experience and discover what you like and don’t like, but these simple truths will get you through the vast majority of the water situations you encounter as a beginner. In Part III, we discuss water in a little more detail for those who decide to mash their own grain.

Bottled Spring Water vs. Distilled and Reverse Osmosis Water

If you spend much time around homebrewers who’ve been at it a while, distilled and reverse osmosis (RO) water will almost certainly enter the conversation. You can think of these as blank canvases of more or less pure H2O that contain very few dissolved minerals. Distilled and RO water are useful tools for brewers who want to “build their own” water from scratch, as is the case for some all-grain brewers whose municipal water supplies aren’t ideal for mashing.

When brewing with malt extract, however, it’s best to steer clear of distilled and reverse osmosis water because they lack the ions and minerals that help enhance flavor and mouthfeel in the finished beer. Regular spring water or drinking water contains a variety of minerals, often balanced in some way to deliver a pleasant experience for the consumer.

Putting It All Together

Just as with cooking a meal, your beer is only as good as the ingredients you put into it. Fortunately, homebrewers enjoy access to a more diverse array of malt, hops, and yeast than ever before, and most municipal water supplies are well-suited for making good beer at home.

Every beer starts with just four basic ingredients. Use the best and freshest you can find, and you’ll be well on your way to making excellent homebrew.

This is an excerpt from our Illustrated Guide to Homebrewing by Dave Carpenter. Want to read the whole thing? Download it here.