If ignorant both of your enemy and yourself, you are certain to be in peril.

— Sun Tzu

———

Do you eat yogurt or drink probiotic smoothies? If so, then you may already understand that there are good bacteria and bad bacteria. The good ones live in our intestines and help digest the food we eat. Without them, we’d be dead. Bad bacteria, on the other hand, cause strep throat, cholera, diphtheria, upper respiratory infections, food poisoning, and other grim conditions.

Similarly, when it comes to beer, there are good microorganisms and bad ones. Sanitation, the first essential step in making beer, is the process by which we destroy as many of the bad ones as we can so that the good ones, the ones we intentionally add to fresh wort, have an opportunity to establish themselves and turn that wort into delicious beer.

Cleaning vs. Sanitizing

Before we can sanitize any equipment, it first must be clean. Clean equipment is just as it sounds: It has been thoroughly washed and rinsed, and it is free of grime, caked-on gunk, dirt, fruit flies, and anything else that ought not be there. Think of it this way. If you wouldn’t eat off of it, you probably shouldn’t brew with it.

Cleaning needn’t be a protracted chore. Just clean your brewing equipment as you would your plates, pots, pans, and other kitchenware. Try to avoid using dish soap, though, as it can leave an invisible film that may destroy the head on your beer later on. Instead, wash your equipment using an oxygen-based detergent. Powdered Brewery Wash (PBW), formulated especially for brewers, is available from virtually all homebrew retailers and is the gold standard for cleaning brewing equipment. OxiClean, another excellent choice, is widely available, highly effective, and very affordable.

In general, a good soak in PBW or OxiClean, followed by a little elbow grease, is sufficient to remove even the most stuck-on fermentation detritus. For especially stubborn grime, or when cleaning hard-to-reach surfaces such as the inside of a carboy, you may need to soak equipment overnight to sufficiently loosen the residue. Hopelessly dirty equipment may benefit from preparing the cleaning solution to a somewhat stronger concentration than you might for normal day-to-day brewing chores. Let experience and your gut be your guides.

Glass and metal equipment can take a reasonable beating, but be especially careful with plastic equipment. Scratches can host unwelcome bacteria, so avoid using stiff brushes and scrapers on plastic pieces. Glass carboys are easiest to clean using the ubiquitous L-shaped carboy brush that comes standard with many starter equipment kits, but think twice before using such brushes on plastic carboys. At the very least, wrap the brush in a chamois cloth before going to town.

Sanitation vs. Sterilization

Homo sapiens is, generally speaking, a lazy species, which is why we today enjoy such modern conveniences as moving airport walkways, fast food drive-thrus, and Amazon Prime. Homebrewers are no exception, especially when it comes to the terminology we use, such as when we say sterilization but mean sanitation. The two are related but not quite the same.

Sterilization means the complete destruction of all living things. Sanitation, however, means reducing a population of living things to an acceptably small number. It’s virtually impossible to sterilize your homebrewing equipment, but, thankfully, it’s also unnecessary. The only time you’re likely to sterilize anything is if you end up really geeking out on yeast culturing. To truly sterilize a piece of equipment usually means subjecting it to very high heat, often with superheated steam, such as in a pressure cooker or autoclave.

Fortunately, sanitation is just fine for what we need to do. Practically speaking, this means that we never completely eliminate any and all wild microbes from the equipment we use. Instead, we use proven sanitation techniques that reduce their numbers to so few that they can’t gain a foothold, and the yeast we add outcompetes them for nutrients.

Common Sanitation Methods

The most common way you will sanitize your brewing equipment is with chemical sanitizers. In the old days, homebrewers often used a dilution of plain old household bleach to sanitize equipment. In a pinch, you can still use it, although there are some very good reasons to avoid chlorine bleach unless there’s no other option. Modern chemical sanitizers are typically acid-based or iodine-based, and, conveniently, require no rinsing. Heat sanitation is less commonly employed than chemical sanitation, but it’s a good option for certain types of equipment.

Sanitizing with Chemicals

Acid-based sanitizers use a blend of food-grade acids to destroy wild bacteria and yeasts. The most popular of these is Star San, which you’ll find in most homebrew stores. Properly diluted, Star San requires only a minute of contact time to effectively sanitize any surface it touches and requires no rinsing once the job is done.

Star San has a legendary tendency to foam up like laundry detergent in a decorative public fountain, and even some experienced hobbyists still get nervous at the sight of all those bubbles gurgling from the mouth of an open carboy as beer drains into it. But, as is commonly exclaimed, don’t fear the foam! It can’t hurt your beer when used at the recommended concentrations.

Another advantage of Star San is that prepared solutions can last for several weeks or months if kept away from heat and direct light. It’s for this reason that many brewers like to whip up a batch of Star San in a spray bottle and spritz pieces as needed. This is especially convenient for those inevitable brief tasks that take place between brew days, when you don’t have a large batch of sanitizer waiting in the wings.

Iodine-based sanitizers such as Iodophor have long been used in dairies and are just as effective as acid-based products. These also require no rinsing and are usually a little less expensive than acid-based products. Some homebrewers avoid them, though, because iodine can (and will) stain any plastic pieces it touches. I personally don’t mind it: In fact, I kind of like that the inside of my fermentation bucket turns a reassuring shade of off-yellow. It makes me feel like I really sanitized the crap out of it. But to each his or her own.

And then there is good old household bleach. Most of us avoid this stuff because chlorine can react with some of the by-products of yeast fermentation to create a class of compounds called chlorophenols, which remind most tasters of plastic adhesive bandages. So, although bleach is an effective sanitizer, I recommend staying away from it (unless you just really enjoy the taste of Band-Aids).

If you forget to buy sanitizer and the homebrew store is closed when you’re ready to brew, then by all means, whip up a batch of diluted bleach solution. But be sure to thoroughly rinse it from your brewing equipment with hot tap water to get rid of as much chlorine as you can. And never allow bleach to touch any stainless steel equipment you own: Over time, it can destroy the surface. And never, ever mix bleach with another cleaner such as vinegar or ammonia. The reaction releases chlorine gas, which is sufficiently toxic that it was used as a chemical weapon in World War I.

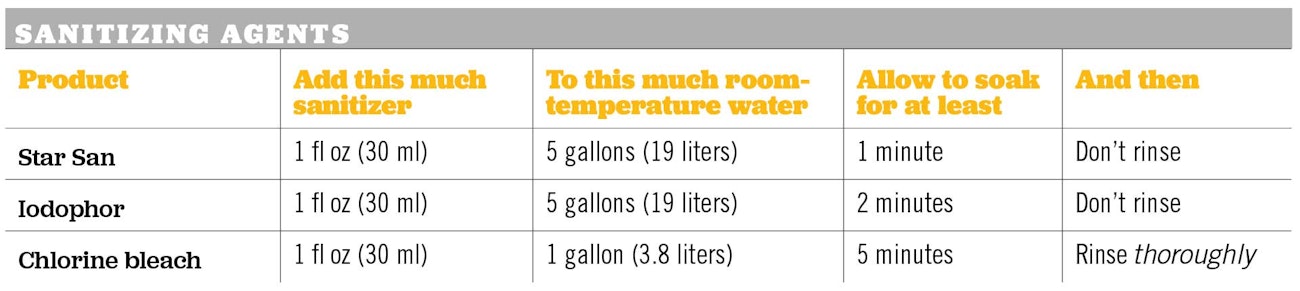

The table above indicates the proper concentrations to use for Star San, Iodophor, and household bleach, as well as how much contact time is needed and whether rinsing is required.

Sanitizing with Heat

Of course, chemicals aren’t the only way to sanitize your gear. Heat does a mighty fine job as well, which is the big reason travelers are advised to boil suspect water in countries that may not enjoy all of the benefits of modern sanitation. Boiling water for just a couple of minutes kills anything that might be lurking on the surface.

You obviously don’t want to boil plastic pieces such as airlocks. I mean, you could, but then you’d just end up with a little wad of plastic that won’t get you very far on brew day. Certain glass and metal pieces of brew gear, though, can be heat treated by boiling:

- Immersion wort chillers (right), which are usually made from copper or stainless steel, are customarily dunked into boiling wort for 10 to 15 minutes to sanitize them. We discuss wort chillers in Chapter 7.

- Stainless steel diffusion stones (see Chapter 8), which some brewers use to inject oxygen into fresh wort, are effectively sanitized using a good rolling boil of tap water.

- Borosilicate flasks (more on those in the next chapter) can be heated right on top of a gas range with a malt extract solution as the first step in propagating yeast.

Glass bottles are probably the most amenable to heat sanitation. If you start them in a cold oven, turn the heat to 350°F (that’s gas mark 4 in the United Kingdom, Thermostat 6 in France, Stufe 2 in Germany, and 180°C everywhere else) and leave them for an hour, you’ll end up with sanitary bottles. Let them cool for half an hour or more, and then they’re ready to receive your homebrewed creations.

Particularly convenient are dishwashers that feature a sanitation cycle. This is the method by which I sanitize all of my glass bottles, and I have enjoyed consistently good results. Truth be told, my dishwasher doesn’t have a specific cycle marked sanitation, but it creates enough steam that I feel it’s close enough. It’s up to you whether that’s an acceptable risk. It is for me, and I’ve had no issues, but your mileage may vary.

When using a dishwasher to sanitize already clean glass or metal gear, run it without detergent on the hottest cycle available, and use the hottest drying setting. Do not use the dishwasher to clean gear, only to sanitize it. Cleaning is best done by hand, as dishwasher detergent presents many of the same head-retention problems as household soap. And running your brew gear through a load with last night’s caked-on lasagna is clearly a bad idea, so just stick to the sink for cleaning and let a detergent-free dishwasher handle sanitation.

Moving On

Maintaining good sanitation practices is the most important thing you can do to ensure reliably tasty homebrew. Take the time to adequately clean and sanitize each piece of equipment you own and don’t be afraid to throw out, recycle, or repurpose pieces of gear that are well-worn and may harbor bacteria. You’ll be doing yourself and your brewer’s yeast a big favor.

This is an excerpt from our Illustrated Guide to Homebrewing by Dave Carpenter. Want to read the whole thing? Download it here.