In October 2021, Tree House Brewing in Massachusetts unveiled Project Find the Limit—a series of double IPAs that gradually, progressively cranks up the dry-hop volume as well as the alcohol and residual-sugar content in each new release. The limit they seek is the “limit of enjoyability”—the idea is to stop when at least 50 percent of polled customers cry “uncle,” as maximum hop saturation tips into something no longer drinkable.

As we go to press, Tree House has released 10 of these IPAs—with recent releases beginning to include liquid hop products—with nary a limit in sight.

The stunt crystallizes how breweries are working to quench the apparently insatiable thirst for greater hop character—but also how, inevitably, there must be a point of diminishing returns. Even as clean lagers and bitter West Coast–style IPAs regain favor, hazy IPAs remain popular among many drinkers—and they have become a vehicle for pushing the limits of hop saturation.

Scott Janish—cofounder of Sapwood Cellars in Columbia, Maryland, and author of The New IPA: Scientific Guide to Hop Aroma and Flavor—compares this era to the early aughts’ “IBU wars.” “Now, it’s more like, how many pounds per barrel are you dry hopping?” he asks.

On some level, drinkers must understand that there are only so many hops that can go into a beer. Bob Grim, cofounder and head brewer at Foam Brewers in Vermont, admits he might be jaded by the savviness of his brewery’s fan base. “The nitty gritty details of the brewing process might not be fully understood, but I think the majority realizes there is a limit to the amount of hops that can be effectively added to a beer.”

Brewers’ ongoing experimentation is in walking that tightrope, pushing the hop-flavor envelope while avoiding potential pitfalls—such as astringency, vegetal character, or hop burn from too much mass, contact time, or over-extraction. Polyphenols yield green, grassy notes, while compounds such as myrcene can contribute onion or too much resin, especially at higher temperatures.

Plenty of brewers are striking the right balance while pushing those limits. How are they doing it?

Choosing Hops Wisely

There is a proven road map for success: Select hops for their promising qualities, then fine-tune whirlpool and dry-hop additions.

Johnny Osborne, who brews his Deep Fried Beers at Alewife in Queens, New York, for the local market, is among those trying to see how far he can push those hop flavors without losing drinkability. When it comes to choosing hops, he looks for desirable compounds. “I’m looking at things [such as] high rates of monoterpene alcohols,” he says. Monoterpenes include geraniol and linalool, which together can contribute floral and fruity notes to beer.

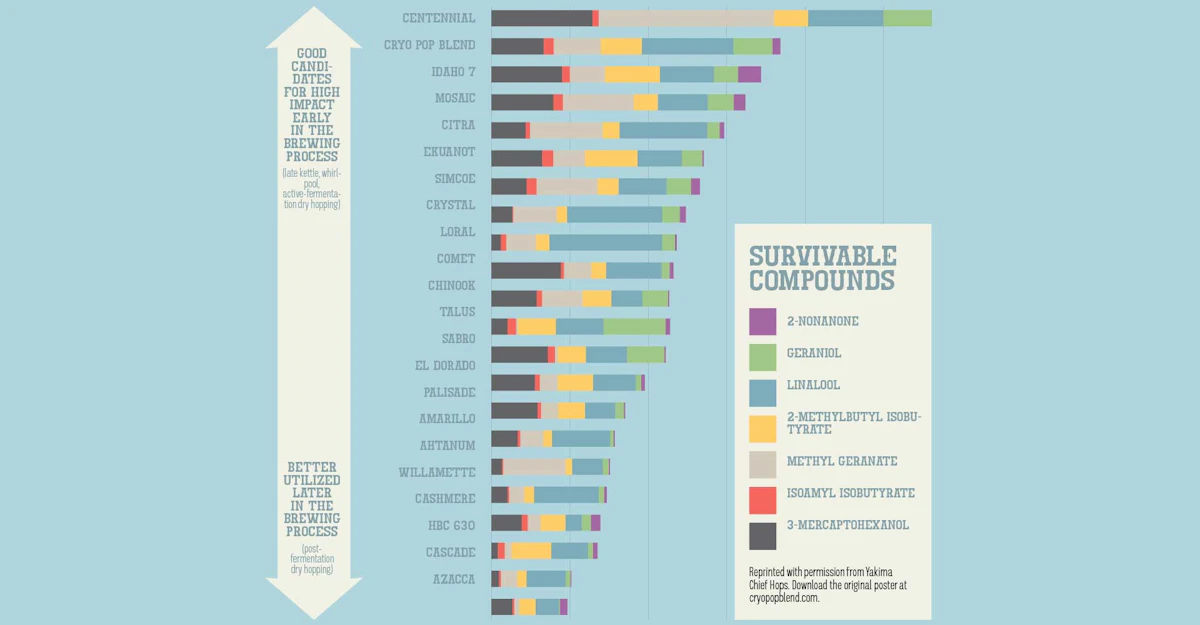

The survivability of these compounds also comes into play—that is, how likely are they to survive the brewing process or how best to preserve them? A Yakima Chief Hops study on “survivables” led to a 30-page Survivable Compounds Handbook. It has become essential reading for brewers willing to dig deeper to get the most from their dry hops (see the chart excerpt from that handbook on page 68).

That Yakima Chief research focused on desirable compounds and in which hops aromas survive the longest and the best, beginning with late-kettle additions. For example: For the floral notes of linalool or geraniol or 2-nonanone’s fruity or herbal notes, hops such as Idaho 7, Mosaic, Citra, Simcoe, and Crystal are strong contenders, usable earlier in the process for hot-side support, in the whirpool, or during active fermentation. Those hops also can be combined post-fermentation with hops such as Sabro, El Dorado, or Cashmere that are richer in more delicate, less “survivable” compounds, providing the opportunity for a more complex bouquet without losing their most promising attributes.

Hop Pellets vs. Hop Products

A growing array of flowable hop extracts, powders, and other such products are available to brewers. Broadly, most are geared toward increasing efficiency and desirable character while reducing hop mass and the risk of associated off-flavors.

Yakima Chief’s Cryo Hops are among the most popular options. Their processing removes the leafy bract of hops to create a more concentrated lupulin product in pellet form. The alpha acids and oils tend to be double or triple what is found in typical T-90 pellets. “You get a lot of the aromatic hop character without the green polyphenol harshness you can get adding [T-90 pellets] to the dry hop,” says Andy Arsenault of YCH’s key accounts division. He recommends using Cryo as a late hot-side addition, in the whirlpool, or as dry hops, starting with 50 percent of the amount of T-90 pellets you would typically add. Many brewers like to blend Cryo 50/50 with T-90s for depth.

Using Cryo pellets means less vegetal matter, and that means less beer waste—less wort soaked up by the hops. That may help the flavor in less obvious ways; Janish says he believes that vegetal matter could also strip out some compounds that you actually want in your beer. He also says that Cryo Hops tend to stay in suspension better, getting a more efficient extraction of aroma and flavor.

Some brewers are also starting to use extracts made from isolated hop oils, which can be separated via fractional distillation into different cuts—such as terpenes or other isolates high in myrcene or humulene. At New Image Brewing in Arvada, Colorado, Brandon Capps is among those who’s been experimenting with isolated terpenes for an aroma boost in conjunction with more conventional hops. However, brewers say the aroma can be powerful—and inelegant, if overused. There is another challenge: The isolates aren’t water-soluble, so keeping them in suspension in beer is tricky. Capps’ way around this is by mixing the oil with a strong spirit, such as Everclear. (For more on this, see Terpenes: Brewing with the Essence of Hops.)

Another product enjoying a lot of recent buzz among brewers isn’t made from hops at all. Phantasm is a powder derived from New Zealand–grown Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc grapes, which are packed with thiol precursors. Thiols are a tiny sliver of the compounds in hop oils, but fermentation can “unlock” them to create desirable tropical aromas (see “The Complex Case of Thiols). Recently, labs have been selling yeast strains that specialize in unlocking those thiols—more on that below.

Phantasm is essentially a hot-side dose of thiol precursors that interact with the yeast in primary fermentation, contributing to tropical aroma. Some brewers say they have found it can amplify the tropical notes of their chosen hop varieties without adding any undesirable aromas—especially when you choose hops higher in thiol precursors, such as Cascade, Citra, Mosaic, Nelson Sauvin, and Simcoe.

Timing Is Everything

Thiols are directly related to a topic that’s been hot for as long as hazy IPA has been cool—biotransformation. Yeast strains interact with hop compounds during fermentation, especially with hops added at whirlpool and early in active fermentation. In recent years, brewers have figured out more ways to get the aromas they want out of that transformation.

Evaluating different hops’ compounds and observing how they change is yet another point of consideration for breweries such as Sierra Nevada, whose Hazy Little Thing IPA has grown quickly to become one of the country’s top-selling craft beers.

“To get really specific with the hop punch we want, we perform dry hopping early in fermentation with varieties that will result in desirable biotransformation effects during yeast contact,” says Karissa Norrington, brewing manager at Sierra Nevada’s plant in Mills River, North Carolina. “Often, this is where we can achieve fruity and tropical notes most consistently in our process.”

Harnessing the potential of thiol precursors and biotransformation ropes in two essential decisions to be made: which yeast strain and when to dry hop. Janish says a product such as Phantasm probably doesn’t reach its full potential unless combined with an appropriate yeast strain, such as Cosmic Punch from Omega Yeast or Tropics from Berkeley Yeast, that produces the necessary enzyme to unlock its potential.

Biotransformation depends on enzyme activity, and that activity depends on the genetics of the yeast strain. Certain strains specialize in producing enzymes such as beta-glucosidase and beta-lyase; the former helps to unlock floral and citrusy monoterpenes, while the latter releases those tropical thiols.

Making the most of biotransformation means dry hopping earlier—as Norrington does at Sierra Nevada—but it’s not a simple calculus. Dialing in what kind of interaction is wanted and at what intensity helps to determine how early to dry hop. However, primary fermentation creates CO2 that also can blow off a lot of positive compounds. Factors to consider include the yeast strain’s biotransformative capabilities, the hops’ compounds, and how much contact time is best.

Whirlpool hop additions have become virtually industry-standard for hop-forward beers, and they represent another way to pack in more flavor and aroma in support of dry hops. At relatively lower temperatures after the boil—typically 160–180°F (71–82°C), though equipment and preferences vary—whirlpool hops add only minimal bitterness, allowing a higher quantity of hops for a flavor punch.

Foam Brewers in Vermont adds whirlpool hops for every hoppy beer, Grim says. However, Foam released a special series of beers—called Spun—to focus on and experiment with the process and communicate its impact to consumers.

“For the Spun Series, we took the whirlpool hop addition to the next level,” Grim says. “We do two separate whirlpool additions back-to-back. We still add ‘the normal amount’ of hops to the first ‘regular’ whirlpool, but then we pump the wort through the heat exchanger and return it to the kettle to drop the temperature below 180°F [82°C].” Since the hops won’t isomerize and add palpable bitterness to the beer below 180°F (82°C), Grim says they can add more hops and get only “the good stuff.” They add four times the quantity of hops they typically do in the whirlpool during this “cool whirlpool,” resulting in a “dramatically amplified hop flavor.”

No Need to Overcomplicate the Dry Hop

When it comes to dry hopping—still the most important technique for promoting hop aroma in IPA—it may be best to keep it as simple as hop selection: Aim for positives and stick with what works.

“I think everyone overcomplicates it,” says Sam Richardson, cofounder and brewmaster at Brooklyn-based Other Half Brewing, one of the country’s best-known brewers of hazy, juicy IPAs. “The biggest factor is contact time,” he says. “Some hops can tolerate longer, some you need to get off the beer sooner. At some point you’ll get diminishing returns. You’re not going to keep extracting positives out of that vegetal matter; you’ll hit a sweet spot, which can be different for different varieties.” For Other Half, ideal contact times range from 48 to 72 hours. No variety offers more aroma past 72 hours, and the negatives grow as you inch closer to two weeks.

For Janish, temperature is key. One of the biggest takeaways that many brewers get from Janish’s The New IPA book is to dry hop cooler for shorter periods of time. At Sapwood Cellars, they dry hop most of their beers around 45°F (7°C), cooler than what was common in the past. Janish says that many hop compounds that can come across as astringent or vegetal tend to extract more efficiently at warmer temperatures. One study he cites found that dry hopping at 68°F (20°C) led to more than double the amount of polyphenols in the finished beer, compared to a beer that had been dry hoppped cooler. Janish says this method allows Sapwood to dry hop “pretty heavily,” getting the compounds they want without the more astringent ones.

In terms of dry hopping “pretty heavily,” Janish finds general treatment of the hops when they’re in the beer—time, temperature, and agitation—more impactful than dry hopping multiple times. A study he references in The New IPA found higher extraction efficiency with multiple smaller additions; now, however, Janish says that Sapwood also has gotten great results with one big dry-hop addition.

What “one big dry-hop addition” means varies brewer to brewer, too. For Deep Fried, Osborne hops at eight pounds (3.6 kg) per barrel for beers such as Trestlemania, which gets Citra, Motueka, Mosaic, Idaho 7, and Comet. At Other Half, Richardson says their beers hover around and above the six-pound (2.7 kg) mark. At New Image, Capps describes a 3.5-pound (1.6 kg) baseline that increases as you climb the IPA ladder—so a “triple dry-hopped” IPA may reach about six pounds (2.7 kg).

Involving Cryo Hops or flowable hop extracts, obviously, can allow a reduced dry-hop charge in terms of weight.

Supporting Characters

Once you’ve formed an entire hopping plan—varieties, product ratios, timing, duration, and temperature—what’s left is how the recipe’s other factors affect how the hops are perceived. As discussed above, yeast is part of that complex equation and should play a role in those hopping decisions.

In The New IPA, Janish describes the importance of balancing the grain bill. In hazy IPAs, for example, brewers promote turbidity with high-protein grains such as oats, flaked wheat, or barley. However, lean too far into high-protein grains, and those proteins can start trapping polyphenols in the beer.

Counter-intuitively, that quality can also help: At Deep Fried, Osborne says that besides boosting that mouthfeel for a hazy IPA, the proteins can help keep terpenes and their more appealing aromas in the beer. As usual, experimentation for the right balance is key.

Water also plays a role in how hops are perceived. Water that’s too high in sulfate or gypsum can dry out the beer, accentuating bitterness but limiting the impact of juicier hop flavors.

At Sapwood Cellars, Janish says, “we’re looking at that chloride and the sulfate ratio, trying to set a stage for a good balance, then understanding that the grains are going to bring a whole bunch more minerals to the table.” Most brewers for these beers are going higher in chloride, Janish explains, targeting 150 parts per million or maybe even higher.

Finally, for breweries of a certain size, centrifuging is an option to help drop out undesirable compounds. Richardson says Other Half was the first hazy IPA specialist to add a centrifuge more than six years ago. Both he and Grim credit its fast, efficient beer-cleaning for helping them to get so many hazy IPAs in desirable condition out the door. Centrifuges remove the floating hop particulate that can cause hop burn. They can also strip some positive flavor compounds, but Richardson says that some finessing can keep removal focused on astringency-causing particles. For lack of a centrifuge, Janish says that Biofine also can help drop out those compounds.

Centrifuges greatly speed up the maturation process that can help all these beers drop their green character and hop burn. With or without expensive gear, a little bit of time is the final piece of the puzzle. That’s why hazy IPAs can vary from being in peak form the day they go in cans to maybe a week after. Preferences vary on when they’re at their absolute best—Richardson finds that three to four weeks out from canning is a high point in flavor melding.

Different brewers will have different time constraints, equipment, and freedom to experiment. However, it’s clear that maximum hop impact without off-flavors is achievable with research and method-tinkering. That’s how innovation works, and it’s pushing the hop flavor of drinkable beers further than anyone thought possible. Drinkers aren’t crying “uncle” just yet.