Bottle conditioning entails dosing a small amount of fermentable sugar and yeast into the beer right before packaging. Sierra Nevada founder Ken Grossman, in his book Beyond the Pale, calls it a “time-honored but rarely commercially practiced” method for creating natural carbonation.

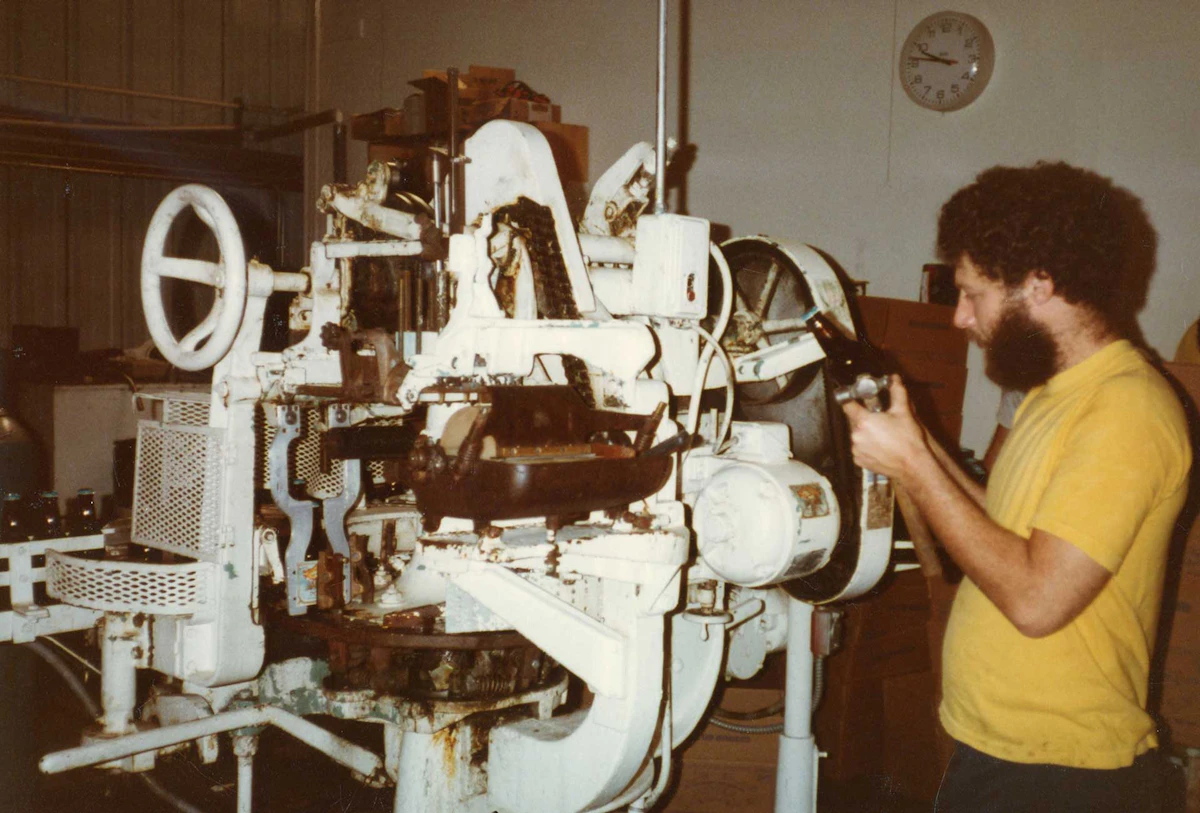

In Grossman’s case, this method was actually his only choice in 1980. He was hand-building his brewhouse with salvaged materials, “and our initial fermenters and aging tanks I welded up [myself], and they were zero-pressure capable.” Any pressure surges in those tanks could mean catastrophic failure. Plus, he retrofitted a soft-drink bottler for his packaging line, and oxygen liked to sneak in.

Bottle conditioning was great for that; it cleaned up the excess oxygen while keeping unwanted compounds such as buttery diacetyl in check. Even more than being a guardian of quality, bottle conditioning refined Pale Ale’s profile with unmistakable nuance that included floral aromatics.

“Part of the bottle-conditioning process is really to create esters and flavor compounds,” Grossman says, “and at the end of the process, hopefully you have all the ones that are desirable [while] the yeast have mopped up the ones that are less than desirable.”

There are considerable trade-offs when bottle conditioning, though. High on the list is time. It takes two weeks after physically bottling Pale Ale to get it out the door. (You could brew another ale, use force carbonation, and release it in that same timeframe.) With that waiting comes the requisite storage space—temperature controlled, mind you, to ensure proper yeast activity—and Grossman knows “that’s beyond the means of a lot of small brewers.”

The outcome itself also has the potential to be sporadic. Your carbonation spec might be a moving target.

“When you bottle condition, unless you’re sophisticated at it, you could be at 2.4 [volumes] or it could be 2.9 [volumes] if you don’t manage your yeast health, your priming levels, your beginning CO2 level at fermentation,” Grossman says. “So there’s a lot of variables in doing it, and you don’t know the number until two weeks later.”

In the early days of Pale Ale, Grossman says, “we did have a lot more yeast getting into the packagings because we didn’t have a filter,” so the results fluctuated. Today, Sierra Nevada bottle conditions with absolute precision. A centrifuge removes residual yeast, then each Pale Ale bottle is dosed with the help of an inline biomass monitor, “and it can tell live [yeast cells] from dead cells,” Grossman says. “So, we can pinpoint exactly how many live cells we want in the bottle-conditioning process.”

The perfect amount of a strain that Pale Ale made iconic: Chico ale yeast, nicknamed after the brewery’s hometown. Its rapid fermentation, reliable flocculation, and distinct flavor have launched countless beers in the last half-century, from homebrewers and pros alike.

“Well, that’s one downside of bottle conditioning,” Grossman says, “is that you’re sending your yeast strain out to anybody who cares to propagate it out of a bottle.”

On the upside, it set American craft beer as we know it in motion. And, this summer, Pale Ale makes packing your cooler easy. Track it down with Sierra Nevada’s Brew Finder.