My first taste of a McIntosh is branded upon my memory. All I’d known before that glorious day was Red Delicious, whose name I’d always felt was at best 50 percent accurate. The McIntosh was different, though, with an intoxicating juxtaposition of sweet, tart, crisp, and juicy. This was nothing like those mealy apples I’d suffered through in my younger years.

Discovering artisanal cider has been equally as revelatory. Far from the generic fizzy apple juice that hides behind the unfortunate name “hard cider” in the United States and Canada (a term unknown elsewhere), craft cider is every bit as sophisticated and nuanced as wine, a beverage with which it shares even more similarity than it does with beer.

From France’s champagne-like cidre brut _and Germany’s thirst-quenching _Apfelwein to tannic scrumpy from England and New England’s fortified winter warmers, there’s a cider for virtually every taste. And let’s not forget perry, cider’s lesser known but no-less-refined sibling. These aren’t just fermented fruits: They’re apples and pears from heaven.

Cider Basics

If you live outside North America, cider means a beverage made from the fermented juice of apples. But, in the United States and English-speaking Canada, the word cider without further designation refers to the cloudy, unfiltered, unfermented juice of freshly pressed apples. An American or Canadian cider seeker in search of the good stuff must usually request “hard cider,” an insult to both the product itself and to the person trying to order it. Perry, the fermented juice of pressed pears, suffers from no such indignity, but you might occasionally hear it called “pear cider.” For the purposes of this discussion, cider and perry refer to the fermented juices of the apple and pear, respectively.

Making cider may appear deceptively simple in that there is no malting, no mashing, no lautering, no sparging, and no boiling: Indeed, there’s no brewing at all (brewing is a term reserved for beer). After apples are picked, they are washed and then crushed into a rough pulp, a process rather onomatopoetically termed scratting. The pulp is pressed through a filter to collect as much of the sugary apple juice as possible, leaving behind a fibrous mass called _pomace. _

After the juice has been liberated from the apples, it is inoculated with yeast (except in certain cases in which unpasteurized juice is allowed to spontaneously ferment) and is fermented for a period of weeks or months. After fermentation, the cider is conditioned, perhaps blended, and packaged. Perry’s process is virtually identical, except pears take the place of apples.

Despite the apparent simplicity of the process, cider makers face challenges that brewers rarely have to deal with. Malt and hops may be purchased at any time, but apples come but once a year.

Up until very recently in the United States, ordering a cider almost invariably meant receiving a rather generic, sticky-sweet product, but as consumer tastes become more refined, new styles are emerging and old styles are coming back from obscurity. A major hurdle to cider making is that Prohibition decimated North America’s stock of cider orchards, leaving behind mainly dessert apples. These make great pie, but they rarely turn out good cider.

“At times, our biggest challenge has been to produce enough quality cider to meet our sales,” notes Diane Flynt of Foggy Ridge Cider, an artisanal cidery in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Flynt’s orchard hosts apples bearing such names as Cox’s Orange Pippin, Muscadet de Berney, and Virginia Hewe’s Crab. These are apples grown specifically for fermentation: In fact, some of the best cider apples are so bitter and tart that cider makers refer to them as “spitters.”

“We planted the first orchard at Foggy Ridge in 1997 with more than thirty cider apple varieties, with the goal of understanding which varieties grow well in our mountain orchards and which cider apples make the best cider,” Flynt says. “Most ciders on the market now are mass market, made from apple juice concentrate or from chaptalized juice (juice that has sugar added) and often consisting of mostly water, sugar, and flavorings. These ciders are packaged and marketed like beer, but if you have good-quality cider apples, there is no need to add flavorings and adjuncts.”

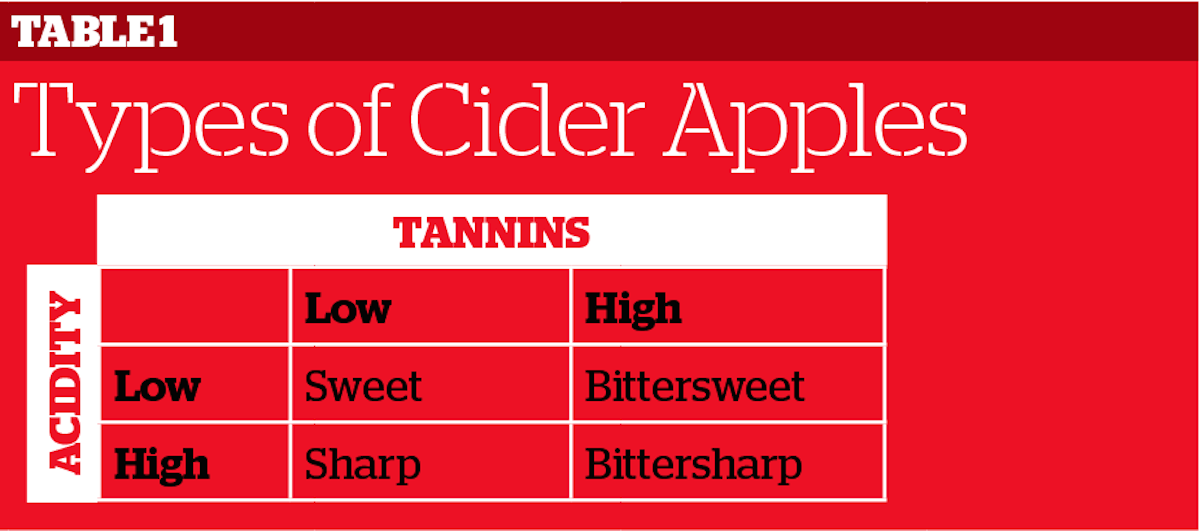

Cider apples are categorized according to the relative levels of tannins, sugar, and acidity they contain (see Table 1). Tannin is responsible for a cider’s dryness or tea-like astringency, acidity provides sharpness on the palate, and sugars offer up sweetness and fermentable sugars. Just as beer brewers manipulate malt and hops to achieve a balance of flavors, cider makers blend different types of apples to create just the right balance of sugars, acids, and tannins.

Aaron Fodge, co-owner of Branch Out Cider in Fort Collins, Colorado, crowd-sources apples from homeowners who register their trees with his company. In the autumn, Fodge and his colleagues head out to private residences to harvest the apples, which are as diverse as the volunteers who contribute them.

“Most American apples are very low in tannins,” observes Fodge. “We’ll frequently bring in up to five or ten percent crabapples to boost the tannins to a level suitable for cider.”

Seasonal variations are also major players. The September 2013 floods that devastated Colorado communities plumped up Fodge’s apple supply, reducing sugar concentrations and delivering a higher than usual water content.

While brewers usually build a recipe from known sources of malt, hops, yeast, and water, cider makers are at the mercy of an agricultural product that is in short supply and of unpredictable temperament. Nonetheless, European and North American cultural traditions have exerted their influence on the ways in which we turn apples and pears into cider and perry.

Cider in Style

As with wine grapes, cider apples express the terroir of their orchards and are sensitive to the whims of microclimate and seasonal weather patterns. Cider styles are as infinitely varied as the land and people that produce them, but we can loosely organize ciders and perries according to their regions of origin.

Common Cider and Perry

The appellation common is given to ciders and perries that are made from standard culinary apples and pears rather than from fruit that has been purpose-grown for fermentation. Apple varieties such as McIntosh, Winesap, Braeburn, and Jonathan make their way into common cider, and common perry relies upon Bartletts, Cornices, and other dessert pears.

English Cider

The British have been making cider since at least the Norman Conquest, possibly much earlier. The West Country counties of Devon, Somerset, Herefordshire, and Gloucestershire are the most prolific, but hardly the only, producers of English cider. In fact, nearly half of all apples grown in the United Kingdom become cider.

The best known English cider, called scrumpy, is produced from a blend of bittersweet and bittersharp apples that are awful to eat but wonderful to ferment. English cider tends to be medium- to full-bodied, with a tannic astringency that can range from a little bit tart to delightfully puckering. A dry, but balanced finish is characteristic, as is an unfiltered cloudiness. Scrumpy can be mildly carbonated, but it’s equally as likely to be served still.

Oliver’s of Herefordshire, Gwatkin, and Wandering Aengus produce full lines of English-style ciders in varying degrees of dryness.

French Cider

French cider is primarily a product of Brittany and Normandy, the latter of which produced William the Conqueror in the eleventh century and today produces cidre and Calvados (apple brandy). French cider may be doux (sweet), demi-sec (semisweet) or brut (dry), with alcohol tending to climb as sweetness drops. Bottled cider is called cidre bouché.

French cider makers practice an unusual technique to create sweet ciders. Through a process called keeving (défécation), the fermentation process is arrested before the yeast has a chance to consume all of the available sugars. In keeving, the cider maker encourages the development of pectic acid from the fruit’s natural pectin. The pectins form a kind of slime—the _chapeau brun _or brown cap—on top of the juice, which traps nutrients. Juice that is siphoned from beneath the brown cap is deficient in nutrients, which stalls fermentation and creates a sweet final product.

Look to Etienne Dupont’s Cidre Bouché and Eric Bordelet’s Sidre Tendre Doux for a bit of Normandy in your own home.

Apfelwein

When we consider German drinking traditions, we usually think of liters of golden lager or tall, hourglass-shaped glasses crowned by fluffy, whipped-cream heads. But in the areas in and around Frankfurt am Main, you’re just as likely to be served a glass of apple wine, or Apfelwein.

Considered the “national drink” of the German state of Hessen, Apfelwein is unapologetically dry, dangerously refreshing, and usually around 5–6 percent alcohol by volume. It may be served still, sparkling, or gespritzt (mixed with sparkling water), and in winter, Frankfurters often heat Apfelwein with cinnamon, cloves, and sugar, and serve it as an alternative to_ Glühwein_ (mulled wine).

Possmann’s Frankfurter Apfelwein sets the commercial standard, and Edwort’s Apfelwein enjoys a cult-like status among homebrewers.

New England Cider

Apples have been part of the American consciousness for nearly four centuries. The Reverend William Blaxton planted North America’s first apple orchard near what is now Boston Common in 1625. Fifteen years later, Blaxton introduced the country’s first named apple variety, the Sweet Rhode Island Greening.

Session-strength cider offered colonists a reliable source of potable refreshment, but in one of the first examples of “imperializing” a style, early New Englanders fortified their everyday cider into something more robust to see them through those brutal Nor’easters. Maple sap, maple syrup, and molasses were readily available sugar sources, and raisins provided an extra boost of yeast. Wooden barrels would have held the concoction until ready for consumption.

New England cider features a discernable apple character, along with the flavors of whatever sugary adjuncts have been added to boost the gravity. Molasses, honey, and maple syrup are typical, but standard table sugar and brown sugar are used, too. Raisins today are less about introducing yeast than they are about contributing flavor and gravity points. And wood aging offers the extra bit of rustic authenticity to get you through the evening’s candle making and witchcraft accusations.

Commercial examples of New England cider include Providence Traditional New England from Nat’s Hard Cider and Blackbird Cider Works New England Style Cider.

Perry

Except that it’s made from pears rather than apples, perry is just like cider—well, sort of. The pear’s chemical makeup (fewer tannins, less acid, and more unfermentable sugar) means that perry tends to be a bit less tart and a bit sweeter than cider. Otherwise, making perry and making cider are very similar processes, and any of the treatments that might be afforded cider can also be bestowed upon perry.

Turn to Eric Bordelet’s Poiré Authentique and Poiré Granit for French takes on the pear and Herefordshire Dry Perry from Oliver’s of Herefordshire to get a British interpretation.

Refreshing Alternatives

France and Britain have long traditions of cider and perry making, but these refreshing beverages are now gaining traction in the United States. If our experience with American wines and craft beers is any indication, though, the innovative fruit-based fermentations we see today are just the first taste—a sweet, acidic, tannic taste that is sure to please anyone who enjoys a finely crafted product.